| Please note that these pages are from our old (pre-2010) website; the presentation of these pages may now appear outdated and may not always comply with current accessibility guidelines. |

| Please note that these pages are from our old (pre-2010) website; the presentation of these pages may now appear outdated and may not always comply with current accessibility guidelines. |

| 2004 is the four hundredth anniversary of the end of the siege of Ostend, one of the bloodiest events of the Eighty Years' War. Described as a 'long carnival of death', it lasted an exhausting three years, two months and seventeen days. A recently donated book to Special Collections provides a contemporary journal of the siege. It is illustrated by uncompromising engravings that graphically illustrate the horrible reality of seventeenth century warfare. |

|

|

The Eighty Years' War (1568-1648) was the war of the Netherlands independence from Spain. Spanish rule had been imposed on the Netherlands in 1519 when Charles V was crowned Holy Roman emperor and king of Spain. Discontent at this rule lead to a revolution in 1567, resulting in the separation of the northern and southern Netherlands. While the south remained Spanish, the north formed the United Provinces of the Netherlands (the Dutch Republic). At war, the United Provinces met with early success in securing Holland and Zeeland, but the union was weakened in 1579 by the defection of the Catholic Walloon provinces. Under the command of Alessandro Farnese, the Spanish had reconquered the southern part of the Netherlands by 1588. In 1598 Philip II granted the sovereignty of the Netherlands to his daughter Isabella and her husband, Archduke Albert of Austria. They continued the war against the northern provinces with the aim of ultimately uniting the Netherlands. Ostend was fortified in 1583 and by the end of the sixteenth century was the only possession of the Republic in Flanders. From this strategically important position, the Dutch could inflict much damage on the surrounding Spanish territory. Even more crucially, control of Ostend meant control of the coast. Therefore, in 1601, Albert decided to besiege the town, stating that he would spend eighteen years doing so if need be. The siege began on 5 July 1601 and became infamous for the heroism, bloodshed and sheer endurance of both sides. As Simoni says, 'among the many battles, sieges, naval encounters and all manner of other military engagements of the Eighty Years' War, none was, and perhaps is, more famous than the long drawn-out siege of Ostend in which the Spaniards assailed the unassailable and the Dutch defended the indefensible'. |

|

Descriptions of the events at Ostend began to circulate a short time after the siege began. This rare printed account was actually produced in three parts between 1604 and 1605. The parts are here bound together with their appendices of illustrations to form a comprehensive account of the whole siege. The full title of Part I of the Belägerung translates as: Siege of the town of Ostend. Journal: diary and truthful account of all the most memorable matters, actions, and events, as they occurred both within and without the world-famous and almost invincible town of Ostend in Flanders, on the side of the defence by the besieged, but on that of the attack by the mighty army of Archduke Albert of Austria, in what way the approaches or advances, sorties, assaults, comings and goings of the ships in the river Geule and the new harbour, all kinds of floating works and buildings for stopping up and blocking the same Geule. Likewise various explosives and new inventions to light them were prepared and executed. Moreover also many unheard-of military tricks and stratagems practised and instigated by both sides, set out in their proper order and followed through from the start of this siege, that is to say from 5 July 1601, until this present autumn fair in the year 1604, and encompassed in two parts, also illustrated and visually presented with fine new copperplates and maps. The whole compiled from the most trustworthy writings to the highest degree of reliability, and published for the service and satisfaction of those who like and enjoy such new accounts, and transferred from the Dutch into the German language and produced in print. - Written according to the most trustworthy writings and newsletters from Ostend and other places, produced in print. 1604. (Translation by Simoni). |

|

|

|

The work is written in plain, unemotional prose and the events are presented in a simple chronological fashion. While the text is in German, the title clearly states that the work was compiled from earlier - mainly Dutch - communications. These were probably manuscript sources that are now lost. Borrowing and retelling accounts in circulation to produce new versions of popular publications was commonplace at this period, and demand for information about Ostend was apparently high. Parts I and II of this version of events were translated into French to produce the booklet entitled Histoire remarquable ... de ce qui c'est passe ... au siege de la ville d'Ostende (Paris: 1604). This in its turn was quickly translated into English by Edward Grimstone to produce A true historie of the memorable siege of Ostend (London: 1604), and was also used by the Leiden printer and publisher Hendrick van Haestens in issuing three Dutch histories of the siege in 1613 and 1614. Other journals were also available, that of Philippe Fleming being the most widely known and used as a source by historians such as Motley. Fleming's account, which appeared in 1621, also draws on Van Haestens, however. |

The journal begins with a geographical description of Ostend's situation and its recent history, emphasising the importance of the town to the United Provinces. The west side was its most vulnerable, but the northern part was protected by a dyke while a new harbour (the Gullet) made the east side almost inaccessible. The town was surrounded by fortifications and protected by a series of strong ravelins. Towards the south west, eighteen fortresses were built by Albert, and in a few months he had fifty siege guns in place; his besieging army numbered about 20,00 men, drawn to the conflict by the offer of inflated pay per day. Within the town, meanwhile, there were about 8,000 fighting men to begin, under the command of Sir Francis Vere; they were a mix of nationalities including English, Scots, Dutch, Flemings, Frenchmen and Germans. |

|

| Frederic van den Berg attacked on the east side of Ostend with the aim of gaining possession of the Gullet, or at least of rendering entrance to the harbour impossible and thereby cutting off supplies to the Dutch. This was almost impossible: the Gullet was a whirlpool at high tide and the Spanish were at the mercy of a Republican fortification called the 'Spanish half-moon' from which cannons and guns constantly shot at them. As Motley laments, 'it was a bloody business. Night and day the men were knee-deep in the trenches delving in mud and sand, falling every instant into the graves which they were thus digging for themselves, while ever and anon the sea would rise in its wrath and sweep them with their works away ... It was a piteous sight, even for the besieged, to see human life so profusely squandered'. |

|

| Despite the exertions of the Spanish, the harbour remained free allowing Dutch skippers to bring in cargoes of supplies regularly. Although provisions were therefore plentiful, conditions in the besieged town were appalling. Many civilians, including women, had stayed on in the town. They faced incessant dangers: their houses burnt down, their belongings were plundered by mercenary defenders and many, of course, were killed or horribly maimed by the daily assaults, sorties, repulses and ambuscades. | |

|

|

Albert made some progress in attacking the western side of Ostend, incurring substantial damage to the town. By Christmas, the besieged had begun to lose men. On 23 December Vere abandoned the external forts; it was a desperate situation as a large assault could not be withstood without the forts. He turned to subterfuge and bought himself time by feigning interest in a truce with the Spanish. The illustration here depicts the doomed negotiations: Isabella and Albert are shown approaching the town, and the immense crowd surrounding them depicts sightseers who apparently came to mock the town while hostilities ceased. As soon as reinforcements arrived, of course, Vere dropped his pretence and abruptly ended negotiations. The siege began again. Vere, however, was recalled from his command because of this unorthodox procedure. |

|

|

|

| This version of the events at Ostend is anonymous and no place of publication is given. According to Simoni, however, it was possibly compiled by one Henricus Bilderbeke and probably printed in Cologne. Bilderbeke was a refugee from Ghent and acted as an 'agent' in Cologne for the States General; he represented the government and obtained information on their behalf. Being placed at the centre of a news network to and from Cologne, it would have been comparatively easy for him to collect material from Ostend. | |

| Much of the power of the work comes from its fine

copperplate engravings 'in which the most outstanding

events are set before all eyes as in a mirror'. These form an integral part of the work and are referred to in

the text. The artist certainly does not spare the reader

the sight of death and destruction and their cumulative effect in

visually depicting the savagery of war overturns the impartiality of the

narrative.

The plate to the right here refers to the fire in Albert's lodging that occurred on 13 November 1601. Its cause was said to be an act of God. A vain attempt to quench the flames by carrying water from the sea in a bucket chain is clearly shown. |

|

|

|

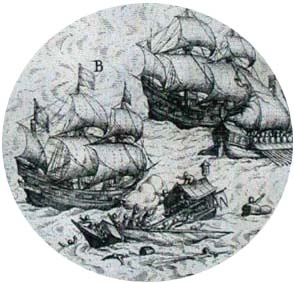

Shown in the plate here are the events of 7 January 1602 when the Spanish forces made their most vigorous and concerted attack yet in an attempt to take Ostend by storm. The Spanish made some early advances, but the Dutch - who had been alerted to the impending assault by spies - put up a determined defence. They opened a sluice which brought seawater rushing into the attackers' trenches, drowning many and sweeping others out to sea. Such was the slaughter that the following day was set aside by both sides to allow the recovery (and plunder) of the dead. The inset in the illustration here shows one intriguing detail from this day. The body of a woman dressed in man's clothing was discovered amongst the Spanish dead; she had evidently taken part in the assault 'as was obvious from certain of her wounds ... under her clothes she wore a gold chain studded with gemstones and also some other valuables and money'. |

|

|

|

|

|

| In September 1603 Ambrosia Spinola assumed command of the Spanish troops. Having studied the situation closely, he decided to concentrate on progressing the western attacks, seeing that the probability of closing the Gullet on the eastern side was slim. Throughout 1604 his campaign slowly encroached on the Dutch defences, aided by ferocious storms in February and March that caused natural damage to the fortifications. Successive commanders in Ostend were killed in action and the Dutch were forced to retreat. The title-page of Part II shows their desperate situation by June 1604. The attackers occupy what had hitherto been the city's outer defensive works and mutual salvoes are being fired from a vast array of guns on either side. The space near the bottom of the picture is inscribed 'Nova Troia': the name of 'new' or 'little' Troy was bestowed on the last entrenchment of the Dutch since they announced that they would hold out there for as long as the ancient Trojans had defended Ilium. Lack of earth meant that dead bodies were used to shore up the ramparts of this final refuge. | |

|

|

By September 1604 the Dutch garrison could not hold out any longer. Since Prince Maurice of Orange's conquest of Sluis in August had made it less essential for the Republic to hold on to Ostend, the States General granted the permission to surrender. The Accord was signed on 20 September and the Dutch marched out without harm, flags flying and drums beating. The articles of capitulation granted the heroic defenders full military honours and Spinola entertained the officers at a magnificent banquet. Albert and Isabella entered Ostend in triumph, but it was a Pyrrhic victory. The town was in ruins and Isabella wept at the desolation. Albert again opened negotiations with the United Provinces and succeeded in concluding a truce for twelve years (1609-21). During this reign of peace and reconstruction he ordered that Ostend should be rebuilt. |

|

This rare book is a recent addition to Special Collections, having

been generously donated by Anna E.C. Simoni, a former graduate of Glasgow

University. Dr Simoni worked for over thirty years in the Department of

Printed Books at the British Library where she founded the Netherlands'

section. She has written numerous bibliographical works on the books of

the Low Countries. Her most recent publication, The Ostend story,

is a study of the various accounts of the siege that were published

between 1604-1605; this copy of the

Belägerung

was used extensively in its research. Dr Simoni also

presented the Library with a copy of this historical study, and the two

books are now shelved together to provide ease of access for their

combined use by future scholars.

The binding of the volume comprises of a fragment of vellum manuscript waste pasted onto millboard. As can be seen from the image of the front cover shown here, the manuscript once formed part of a Gospel Lectionary; it is written in a Textura script and probably dates from the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Century. Of further interest in tracing the book's history is the label of the "Bibliotheca di S.A.R. il Duca di Genova" found on the front pastedown; the Duca's book stamps are also found on the title-page (seen in purple ink in the second illustration above) and on several other pages throughout. Which Genoese doge the book belonged to has not yet been identified.

|

|

|

Return to main Special Collections

Exhibition Page Julie Gardham March 2004

|