Book of the Month

December 2008

The Bookman

Special Christmas Number, 1918

London: 1918

MS Farmer 348/5

The 11th November 2008 marked the 90th anniversary

of the Armistice that brought the First World War to a close. Our

choice for December's Book of the Month returns to the first year of

that long-awaited peace with a feature on

The Bookman, Special Christmas Number, 1918. This issue

went to press in the month following the end of the

most destructive war in British history to date. In a feature-length

Christmas supplement, The Bookman periodical brings together a

variety of articles and reviews to pay tribute to the literary

heroes of the war.

|

Front cover of The Christmas Edition, 1918 |

The Bookman

was a monthly literary periodical devoted to "Book buyers, Book

readers and Book sellers." It was established in 1891 by the

Aberdeen-born William Robert Nicoll, a liberal journalist working in

London, and ran until 1935 when it was absorbed by the London Mercury.

A middlebrow publication, priced at 6d, it was intended to appeal to

aspirational readers with limited disposable income. It offered book

reviews and colour illustrations as well as longer pieces of literary

criticism and special features on authors. The formula proved

commercially successful and became a platform for the publication of

early work by writers such as J. M. Barrie and W. B. Yeats.

The Bookman was, of

course, also an important advertising vehicle for its publishers Hodder & Stoughton, featuring many adverts and current publication

lists.

The annual Christmas Double Issue edition became a

popular institution, with its feature-length children's literature

supplement and colour illustration plates by notable artists.

Typically festive and colourful, it was the highlight of

The Bookman's publishing year. However,

after four years of war, the 1918 Christmas edition adopted a more

sombre tone, reflecting the solemnity of a bereaved nation. The

Christmas issue of 1918 focused instead on the significant literary

output of the war. The war touched every area of human consciousness

and literature proved no exception. In fact, in an age when poetry

formed an important part of the cultural diet of the population, the

First World War proved a great literary phenomenon. In the early

stages of the war, in August 1914, the Editor of

The Times was receiving 140 unsolicited poems a day for

publication. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cover pages from other

issues of The Bookman

|

|

Christmas Double No,

December 1911

(Stack Gen Hum Pers Vol. 41) |

October 1912

(Sp Coll Whistler e1.20) |

October 1911

(Stack Gen Hum Pers Vol. 41)

|

|

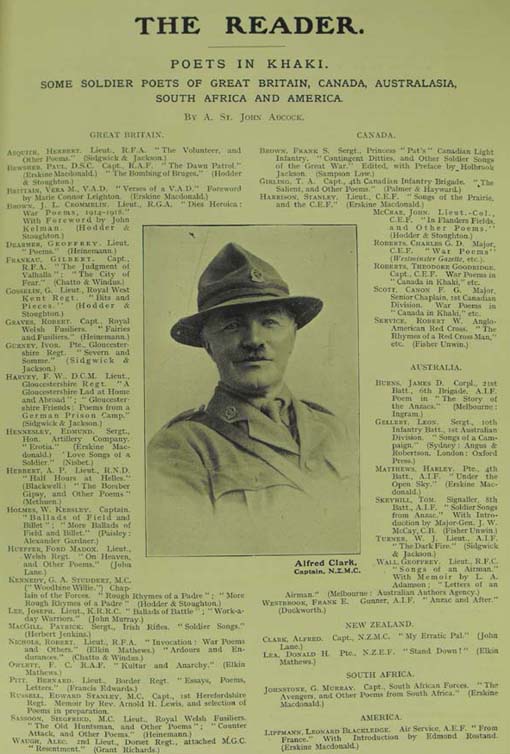

"Poets in Khaki," page 83 |

The first page of the supplement opens

with a printed memorial to the writers of the war. It reads as a Roll of

Honour, mimicking the form of stone memorials to fallen soldiers that

became so common during, and particularly after, the war. These

memorials became an iconic

aspect of the Great War legacy. The Imperial War Graves Commission

made the decision that bodies should remain where

they fell, and be interred in military cemeteries. Unable to access loved one's

graves, memorials provided an important substitute in the grieving

process. In

Britain, where one in six families suffered a bereavement, temporary

community memorials, roadside calvaries and monuments sprung up all

over the country. They expressed the desire for remembrance in the

aftermath of the war, with permanent memorials

forming the cornerstone of Remembrance Day and Memorial Ceremonies.

The use of names on memorials - a practice that had grown throughout

the 19th century - became almost universal in the Great War.

Prior to this, war memorials were intended to celebrate military

victories rather than mourn the dead, and rarely bore the names of the

fallen. In a century of devastating warfare, memorialisation

moved increasingly towards the commemoration of the dead and the recording of individual names

was adopted in an effort to find consolation and meaning. The largest

example of this was British architect Sir Edward Lutyen's Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the

Somme bearing the names of 73, 367 missing, presumed dead, Allied

soldiers. Here, this practice is replicated in print form as the names

of war writers, both surviving and fallen, are presented alongside

the titles of their major works. |

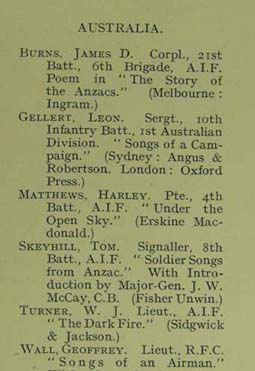

As well as British writers, the supplement also

prints contributions from several different nations. Included are poets from America, Canada, South Africa,

Australia and New Zealand, acknowledging Britain's debt to her

Imperial and Commonwealth forces and the wider international community of

volunteers such as the French Foreign Legion and American recruits. This reflects the significance of the Great War as the

world's first truly

global conflict in which some 30 plus nations took part. |

Detail from "Poets in Khaki"

memorial |

The writers honoured in this roll call are discussed

in further detail in the editorial piece "Poets in Khaki" by St. John Adcock. This

article of literary criticism offers a contemporary

perspective on the literature of the war and indicates that the war

generation were already aware of the lasting significance the

"enormous body of verse, touching on... infinitely varied aspects"

was to assume. It provides a detailed account of

the writing the author considers to be the most prominent, interspersed with portrait plates,

photographs and tributes to various writers who served in, and wrote

about, the war. In doing so, this article presents several writers of

the war who are now largely unread by modern

audiences. |

|

One such writer is the American Alan

Seeger. Now considered a relatively minor poet, his writing

captures that initial

spirit of idealism and enthusiasm so prevalent in the early war years. As a volunteer, it was the same sense of "triumphant

idealism" which St. John Adcock notes in Seeger's writing that

prompted him to sign up. With America officially neutral until 1917, Seeger joined the French Foreign Legion in a bid to reach the

Western Front. His poem, "Ode in Memory of the American Volunteers

Fallen for France," which is quoted at length in

The Bookman, perfectly sums up this sense of

romantic idealism. When "Europe's bright flag of freedom"

is threatened, he is eager to jump into the fray:

"Now heaven be thanked, we gave a few brave drops;

Now heaven be thanked, a few brave drops were ours."

The same longing for the perceived glamour and adventure

of war is also present in Seeger's most famous poem, "Rendezvous," in

which he eerily predicted his own death:

"I have a rendezvous with Death

On some scarred slope of battered hill,"

Seeger was to die, caught in machine gun fire, in July 1916. This welcoming of death displays a

touching naivety now ruefully associated with the Great War. These poems are similar in sentiment

to Rupert Brooke's sonnets, and perhaps suggest the

reason why Seeger's work is today not as popular as it was during the

war. It represents an earlier innocent

enthusiasm that seems so sadly ironic in

retrospect of the carnage that was to come. However, this mode of

writing was soon to give way to an unprecedented sense of realism

in war writing. As St. John Adcock goes on to show, the portrayal

of the "seamy" side of war continued to grow as idealism gave way

to disillusionment and a desire to "reveal the naked horror of the

realities" of battle. |

Alan Seeger, illustration plate, uncredited

|

|

|

Leon Gellert, portrait plate,

photo by May Moore |

The epitome of what St. John Adcock describes as the "seamy"

representation of war can be found in the writing of Leon Gellert,

who was "terribly conscious of that revolting, inglorious underside

of war." Gellert, from Adelaide, was posted to Gallipoli after the

outbreak of war, but developed dysentery and septicaemia after three

days of solid fighting. He was discharged from army, but his

experience of the horrors of warfare found its way into his verse.

In "Songs of a Campaign" he chose to depict the effects of warfare

on the men who fought. His war poetry portrays grit, disillusionment

and "the piteous wreckage of humanity" in verses about the ordeal of

the soldier such as "The Attack at Dawn" and "Before Action," or the

after effects of war in "The Cripple," or "The Blind Man." In fact,

his writing is emblematic of the disillusionment that extended warfare brought,

and similar in tone (if less satiric) to that of the British poet

Siegfried Sassoon.

This type of anti-romantic war poetry was one of the great

revelations of the First World War. Where, in the past, an

idealistic language of noble and heroic battle had dominated war

writing, the First World War was said to have shattered notions of

heroism. St. John Adcock attributes this shift of perspective to the

mass conscription of the Great War, where armies consisted of

recruits rather than professional soldiers. |

|

John McCrae in uniform, photo uncredited |

St. John Adcock touches on another Commonwealth

writer who responded to the tragic side of warfare. Canadian writer

John McCrae's "In Flander's Fields" is one of the more famous

poems of the war, still often used in Memorial Day Ceremonies, with

the opening lines:

"In Flander's fields the poppies blow,

Between the crosses, row on row".

It

employs typically elegiac conventions in offering pastoral consolation for the bereavement of

war. The poppies McCrae iconizes in his poem have become emblematic of the Great

War, and were chosen in 1921 as the most fitting symbol for the

British Legion's Poppy Appeal.

McCrae, a Canadian writer and doctor of Scottish Presbyterian

extraction, served as a medical officer in the war. He composed his famous poem during the Second Battle of Ypres

in 1915,

allegedly on a scrap of paper in the trenches in response to the death

of a comrade, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer. McCrae died of pneumonia on

the Western Front in the January of 1918, and is himself, now buried in one of the 2500 British military cemeteries in

Flanders. |

|

Another Commonwealth writer to whom Adcock turns is

Robert Service. Although labelled the

"Canadian Kipling," Service was born in Lancashire, and

raised in Hillhead in Glasgow.

He attended the newly-founded Hillhead Boys School, site

of the current Hillhead High - a fact commemorated today by a

plaque on site. He fostered dreams of becoming a cowboy in the days of Gold

Fever and emigrated to Canada aged 22 with just $5 in his

pocket. His appetite for travel and adventure was unquenched, however,

and his days were spent travelling the world. Living in Paris at the outbreak of the war, he joined a band of

volunteer American ambulance drivers. Despite his non-combatant role,

he experienced heavy shelling, and frequently came under fire. He recorded his

first-hand observations of war

in

Rhymes of a Red Cross Man. His

accessible style reached a mass audience in America and topped

bestsellers lists. In fact St. John Adcock claims in

The

Bookman "No Canadian poet has a wider popularity with

civilians and soldiers than Robert Service. I have heard ballads of

his recited in huts behind the lines in France." He quotes "Song of Winter

Weather" to demonstrate Service's popular touch

"No it isn't the guns,

And it isn't the Huns -

It's the MUD,

MUD,

MUD."Service's colloquial style emulated, and appealed to, the

common soldier. Yet it also conveyed the realism of day-today

conditions in the trenches rather than the excitement of battles

and charges.

Strangely, though originally immensely popular, Service's poetry and novels are now rarely read,

and his autobiographies are largely out of print. Perhaps one reason for this is that

his light-hearted humour and optimistic approach to the war appears,

in the eyes of modern-day readers, to trivialise the war. |

Robert Service, portrait plate,

photo by J. Kennedy |

|

Another writer popular at the time, and

especially with the troops, was Geoffrey Anketell Studdert Kennedy, more commonly known as Woodbine Willie.

A British parish priest, Reverend Studdert Kennedy served as a

chaplain in the British Army. He was extremely popular amongst

the troops for his compassion and courage in braving the front

line to help wounded and dying men. His nickname was bestowed

upon him for his habit of doling out the cheap and popular

Woodbine brand of cigarette that was favoured by the forces.

Woodbine Willie authored

Rough Rhymes of a Padre, a collection

of popular and humorous

rhymes as opposed to high literary output. Like Service,

his use of the vernacular

approximated the speech of the average grousing Tommy. |

"Woodbine Willie" photo by W. W. & R. Dowly

|

|

|

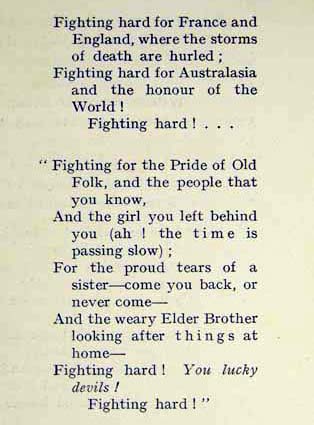

Detail from page 87, from "Fighting Hard" by C. J. Dennis |

The Australian equivalent of Woodbine Willie and

Robert Service was C. J. Dennis, "probably the most popular Australian

poet today," according to St. John Adcock. Although he didn't

serve in the army, his poetry dealt with the issue of the war. He

produced verse in a colloquial Aussie dialect through his characters,

such as Ginger

Mick and Doreen. "I suppose you fellers

dream, Mick, in between the scraps out there

Of the land yeh left be'ind yeh when yeh sailed to do yer share"

His writing was popular with the home audience for

some 50 years, and the initial print run for Songs of a Sentimental Bloke

of 40,000 - unheard of for poetry - sold out almost

immediately. It was lauded as the Australian troops' "trench bible" and

sold well in pocket editions small enough to carry to the trenches.

His writing is declared the "quaintest, liveliest, most picturesquely

colloquial of Australian war ballads" in

The Bookman, filled with "humour and

pathos." On Dennis' death, the Australian Prime Minister called

him the

"Robert Burns of Australia" for his canonisation of the Australian dialect

into literature. |

|

John Buchan, detail from title cover,

portrait

photo by Bassano |

The Bookman also pays tribute to the venerable

Scottish writer and Glasgow University graduate John Buchan in a

separate article by David Hodge, entitled "John Buchan as War Historian." Regrettably this section is missing from

Special Collection's copy of The Bookman,

and may have been torn out by the previous owner of

the periodical, Henry Farmer. Perhaps, as a fellow resident of

Glasgow, this article was of particular interest to Farmer or his

associates.

Buchan had several roles during the war. Unfit for service due to

a

lifelong health issue with stomach ulcers, he was instead given a notable role as Director of

Information at the War Office. He visited the Western Front twice, and was

involved in the authoring and dissemination of propaganda. He was also

a celebrated fiction writer whose spy-catcher series - including titles

such as The Thirty-Nine Steps and

Greenmantle - spanned

the war years. The focus

of the article, however, is Buchan's work as the principle writer on

the contemporary serial,

Nelson's History of the War, which recorded the history of the war

as it was happening. Hodge praises the "lucidity" of the history

serial, which explains complex military operations simply and adopts a

cool perceptive tone. He declares it to be as readable as Buchan's

fiction. |

| The Bookman's

supplement on the literature of the war is an original document

from a period that still fascinates current generations. It offers

a contemporary perspective on writers who were read by those who

lived through the war, offering us poets that have long-since

fallen into obscurity. The Big Name poets of Wilfred Owen,

Isaac Rosenberg and Rupert Brooke who today dominate the landscape

of First World War poetry, are notable in their absence. The Great

War will soon pass out of living memory and valuable sources such

as this will soon prove to be our only link to the past and the

attitudes of those who lived through such an epoch-making period. |

|

Detail from the front cover |

|

|

Other items of interest

John Buchan A History of the Great War

London: Nelson 1921, 1922

Level

8 Main Library History BM 170BUC vol. 1-4

Robert Service

Collected Poems New York: Dodd, Mead, 1961

Level 9 Main Lib English NS210 1961

The Bookman, October 1912, Portrait of

Whistler Level 12 Main Lib Sp Coll

Whistler e1.20

The Bookman,

volumes 7, 9, 10, 15-18, 36, 38, 39, 41, 63, 68

Library

Stack Main Lib

Gen Hum Pers

The following have been useful in compiling

this article:

Philip Butterss, "C. J. Dennis"

Dictionary of Literary Biography Volume 260 Australian Writers

1915-1950, edited by Selina Samuels. Detroit, London:

Gale Research Group, 2002

Level 9 Main

Lib Gen Literature

qE10 DIC Vol 260

Niall Fergusson

The Pity of War London: Allen Lane 1998

Level 8 Main Lib History BM100 FER

Paul Fussell The

Great War and Modern Memory Oxford: Oxford University Press 2000

Level 9 Main

Library English E478.W2 FUS

Carole Gerson, "John McCrae" Dictionary

of Literary Biography Volume 92 Canadian Writers, 1890 - 1920 Edited

by W. H. New Detroit Michigan London?: Gale Research Group, 1990

Level 9 Main

Lib Gen Literature

qE10 DIC Vol 92

James A. Hart, "Alan Seeger" Dictionary

of Literary Biography Volume 45 American Poets, 1880 - 1945 Edited

by Peter Quartermain Detroit, London:

Gale Research Group/Bruccoli, 1986

Level 9 Main Lib

Gen Literature

qE10 DIC

Vol 45

Samuel Hynes A War

Imagined; A War Imagined: The First World War and English Culture

London: The Bodley Head, 1990. [Not in Glasgow University Library but

available in

the Mitchell Library,

942.08370 HYN]

Alex King

Memorials of the Great War in Britain Oxford, New York:

Berg 1998

Level 8 Main

Library History BM 1770 KIN

Carl F. Klinck & W. H. New, "Robert

Service" Dictionary of Literary Biography Volume 92 Canadian

Writers, 1890 - 1920 Edited by W. H. New Detroit Michigan London?:

Gale Research Group/Bruccoli, 1990

Level 9 Main Library

Gen Literature

qE10 DIC Vol 92

James MacKay Robert Service, Vagabond

of Verse Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 1995

Level 9 Main Library

English NS211 MACKA

Janet Adam Smith

John Buchan: A Biography London: Hart-Davis, 1965

Level 9 Main Library

English NB751 SMI

Jay Winter Sites of Memory, Sites of

Mourning Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995

Level 8 Main Library

History BM1770 WIN

"Introducing: William Robertson Nicoll" by Jason Goroncy

at Wordpress,

http://cruciality.wordpress.com/2008/07/15/introducing-william-robertson-nicoll (page accessed 19/6/08)

Return to main Special Collections

Exhibition Page

Go to previous

Books of the Month

Aimee Cook (Graduate Trainee

on placement in Special Collections), December 2008

|