Political Theatre in Scotland

Adrienne Scullion

Scotland’s playwrights and theatre makers have a long history of being politically engaged and socially provocative, indeed for some the definitive form of theatre in Scotland is political theatre.

Satire

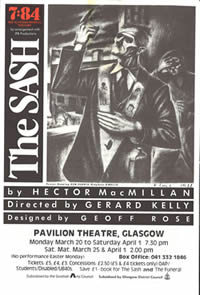

Sir David Lindsay’s Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis (1540, 1552, 1554) is the most innovative and celebrated theatrical text of the Scottish Reformation. The play is the masterpiece of C16 Scottish culture and is a sustained critique of political will and political process: above all the play is about the type of court and the type of society that Lindsay aspired to for Scotland. Irreverently satirical in its day, the play’s very immediacy – its politics and its late-Medieval theatrical form – meant that it fell quickly out of ideological and theatrical fashion and, when the play was finally revived for the 1948 Edinburgh International Festival, the values it sought to represent, the values it sought to promote, were very different from the play’s particular and political purpose at the sixteenth-century Scottish court. Instead of a play seeking to influence contemporary policymaking and policy makers, its twentieth century manifestations have been significantly denuded of politics: for some critics the twentieth-century revivals in Edinburgh are damned as little more than ‘a fancy-dress affair’. But, if The Three Estates has struggled to demonstrate C20 and C21 relevance, it is certainly the case that satire remains a repeated and a familiar trope in twentieth-century Scottish theatre: Joe Corrie’s And so to War (1936), Robert McLellan’s The Flouers o’ Edinburgh (1948) and Hector MacMillan’s The Sash (1973) were all important and influential satires, while Iain Heggie’s scabrous King of Scotland (2000) was an indecorously post-Devolution deployment of Gogol’s short story The Diary of a Madman presented as a breathtakingly obscene and a viciously satirical monologue.

Socialism

The 1920s and 1930s saw a huge increase in the amount of theatre being made in Scotland, in particular at grassroots, local and community-level. One of the most significant theatre groups of the time was the Glasgow Workers’ Theatre Group. With an interest in telling stories of working-class relevance, and telling them in challenging new ways, GWTG’s theatrical style was bold, committed and identifiably political. The company’s great successes included: the first British production of Waiting for Lefty, Clifford Odets’s notorious new play of the dispossessed working class in New York; anti-fascist masques and pageants about the Spanish Civil War; mass declamations and living newspapers; and, UAB Scotland, a play from 1940 by group member Harry Trott. Like all good political theatre UAB Scotland (the acronym stands for the Unemployed Assistance Board) urgently demands the active involvement of the audience. Much of the text is presented in direct address and it is full of references to contemporary political issues, primarily the economic crisis on Clydeside.

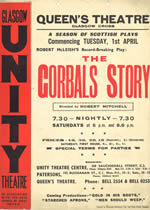

UAB Scotland was GWTG’s last production before it joined with four other leading left-wing amateur companies in Glasgow to form one of the most significant of Scottish political theatre companies, Glasgow Unity, a company that commissioned and produced important new plays by local writers that explicitly concerned the lived experience of ordinary people. Unity’s splendid catalogue of new writing includes Ena Lamont Stewart’s Starched Aprons (1945) and Men Should Weep (1947), and Robert McLeish’s The Gorbals Story (1946).

Many of Unity’s plays are celebrated not just for their politics but for a caustic Glasgow humour – this popular connection is often seen as another distinctive feature of Scottish dramaturgy. Perhaps the best example of Scottish popular political theatre is The Cheviot, the Stag and the Black, Black Oil, a play written by John McGrath in collaboration with members of the company 7:84 Theatre Company (Scotland) and first toured across the Highlands and Islands in 1973. The Cheviot was a production that changed and revitalised political theatre within Scotland – it changed where theatre went and what it was about. 7:84 toured The Cheviot to village halls, school halls, church halls, playing to different types of local community audiences in the places where they lived. The Cheviot proclaimed itself as a ‘people’s history’ – and claimed authenticity through its archive research and use of primary sources. There was excitement and there was emotion at performances. Audiences felt that the company was talking about them, about their history and their experiences.

Feminism

With some very notable exceptions women are disproportionately under-represented in leadership roles in Scottish theatre. Nevertheless there is a strong raft of modern plays that place women at their centre and that advocate a politics of feminism.

Sue Glover’s 1991 play Bondagers recollects the lives of the peasant women who worked as cheap agricultural labourers in the border farms of the nineteenth century. The play follows one year in the lives of six women working the land under this system. It is told in a vivid, energetic and poetic style. Like The Cheviot it draws on Scottish popular traditions of story-telling, song, dance and music.

Liz Lochhead’s 1987 play Mary Queen of Scots Got her Head Chopped Off again places women at the centre of the narrative. Like all good history plays Mary Queen of Scots uses the past to make clear and political comment on the present. Lochhead’s ‘history play’ is littered with anachronism and incongruity: twentieth-century props (prams, telephones and bowler hats), music, rhymes and games; and explicit parallels with contemporary British politics. Mary Queen of Scots retells history from a previously marginalised female perspective. But because Mary Queen of Scots is also a play of the 1980s – it has a job of work to do in the politics of the 1980s – not least in its dramatisation of oppositions, the ‘us and them’ tension – of Scotland not being England – that seems to underpin so much of the theatre culture of that time.

Some have argued that this oppositional dynamic played a crucial role in how artists sought to reframe of Scottish national identity. It has certainly been seen as a factor crucial in representations of devolution and in theatre that explored independence.

Nationalism

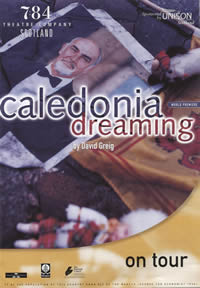

Peter Arnott’s A Little Rain was premiered in 2000 in the immediate post-Devolution context by 7:84. A Little Rain was the third play in a loosely connected trilogy of politics plays commissioned by the company’s then artistic director Iain Reekie that began with David Greig’s Caledonia Dreaming in 1997 and Stephen Greenhorn’s Dissent in 1998. The frustration felt by politicised writers, like Arnott, with the early reality of post-Devolution Scotland was matched by a realisation, articulated in A Little Rain, that a new democracy demanded not just ‘the same old’ solutions but a revised new world view.

What was required was a view of Scotland that explored the tensions inherent in the Devolution agreement for Scotland to be impact-ful within the nation and aspirational outwith it, to find solutions within but have a role externally and in partnership with others. The politics and the identities of post-Devolution have been sought for and explored in a wide variety of political dramas: through the vicious satire of Iain Heggie’s King of Scotland; through the allusive metaphor of Nicola McCartney’s Home; the subtle allegories of David Greig’s Pyrennes; the black humour of Henry Adam’s The People Next Door; and, the heightened realism of Davey Anderson’s 2005 play Snuff. Paralleling work in the contemporary Scottish novels – for example work by Irvine Welsh and Christopher Brookmyre – humour and black comedy – even more than satire – has emerged as a common feature of the political drama of contemporary Scotland: with plays by Douglas Maxwell, Henry Adam and Gregory Burke leading the way. In Gregory Burke’s 2001 play Gagarin Way a kidnapping goes violently wrong.

The play absolutely obeys the rules of Scottish popular theatre: it is highly topical; rooted in a clear and particular locality; adopts a demonic vernacular; and is infused by a larger and inclusive world view that sees the economic decimation of one small town Scotland as part of a the economic processes of globalisation.

Further Reading

The Twelve Seasons of the Edinburgh Gateway Company, 1953-1965 (Edinburgh: St Giles Press, 1965).

Ian Brown, Scottish Theatre: Diversity, Language, Continuity (Amsterdam / New York: Rodopi, 2013).

Donald Campbell, A Brighter Sunshine: a hundred years of the Edinburgh Royal Lyceum Theatre (Edinburgh: Southside, 1983).

____, Playing for Scotland: a history of the Scottish stage, 1715-1965 (Edinburgh: Mercat, 1996).

Maria Di Cenzo, The Politics of Alternative Theatre in Britain, 1968-1990: the case of 7:84 (Scotland) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Michael Coveney, The Citizens’: 21 years of the Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre (London: Nick Hern, 1990).

Terry Lane, Side by Side: The Traverse Theatre (Castiglione del Largo: Edizioni Duca della Corgna, 2007).

John McGrath, Naked Thoughts That Roam About: Reflections on theatre. Edited by Nadine Holdsworth (London: Nick Hern Books, 2002).

____, A Good Night Out: popular theatre, audience, class and form (London: Eyre Methuen, 1981).

____, The Bone Won’t Break: on theatre and hope in hard times (London: Methuen, 1990).

Elizabeth McLennan, The Moon Belongs to Everyone: making popular theatre with 7:84 (London: Methuen, 1990).

Joyce McMillan, The Traverse Theatre Story, 1963-1988 (London: Methuen, 1988).

Valentina Poggi and Margaret Rose, eds, A Theatre That Matters: Twentieth-Century Scottish Drama and Theatre; A Collection of Critical Essays and Interviews (Milan: Edizione Unicopli, 2000).

Trish Reid, Theatre & Scotland (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

Steven Unwin, Jenny Killick and A Pollock, eds, The Traverse Theatre, 1963-1988 (Edinburgh: Traverse, 1988).

Donald Smith, ‘1950-1995’, A History of Scottish Theatre ed. Bill Findlay (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1998), pp. 253-308.

Randall Stevenson and Gavin Wallace, eds, Scottish Theatre since the Seventies (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996).

001_350.jpg)

_150px.jpg)

_150px.jpg)

_150px.jpg)