Scott, Rob Roy and the National Drama

Alasdair Cameron

For much of the nineteenth century, theatre in Scotland was dominated by the Theatre Royal, Edinburgh. 'It was here that the phrase 'national drama' was invented to appeal to the patriotism of the prosperous citizens of the Scottish capital. From that 'national theatre' an influential repertoire emerged ensuring that Scottish writers, especially Sir Walter Scott, were responsible for some of the most frequently revived works on the English stage.' The nineteenth century theatre's thirst for dramatic novelty, stimulated by the lengthy programmes offered each evening, meant that every corner of Scottish literature and history was ransacked to provide mainpieces, curtain-raisers, afterpieces, pantomimes and harlequinades.' The subjects chosen ranged from the obvious, like Mary, Queen of Scots, to the seemingly unstageable, such as Tam O'Shanter. The 'national drama' was the fullest expression of this world and work. The term described any play with a historical Scottish setting, usually adapted from a novel by Sir Walter Scott, and containing liberal sprinklings of Scottish music, Scottish dancing, spectacular scenery and tartan soldiery.' Scott himself was actively and weightily involved in the affairs of the theatre and numbered W H Murray, its manager from 1815 to 1851, as well as many of the best actors, amongst his friends and he championed performances of works by other Scottish dramatists, notably Joanna Baillie. [...]

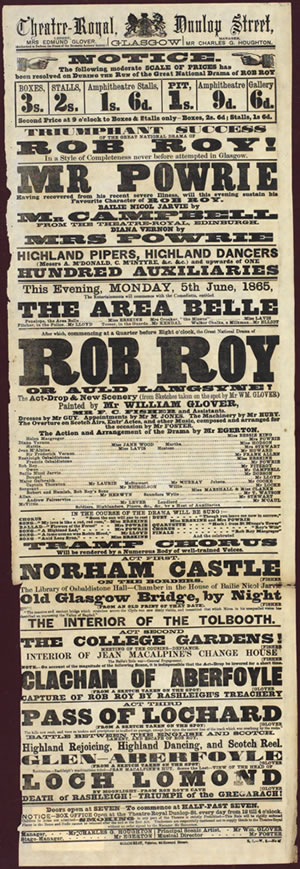

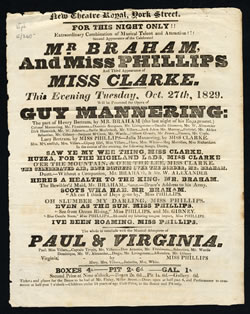

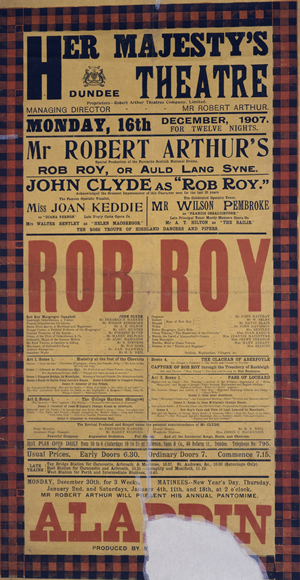

The vogue for stage adaptations of Scott's novels really began with Isaac Pocock's Rob Roy MacGregor, in 1818, but before that, there had been many attempts to get the formula right.' The most successful of these had been William Terry's 'Terrifications', as Scott called them, of Guy Mannering.' The Lady of the Lake had also proved a popular source, even though its first performance in Edinburgh in 1810 when it was produced as a lavish spectacle, with 'views taken from life', had been a failure, in spite of being widely advertised and eagerly looked forward to in the newspapers. 'By the time Scott died in 1832, most of his novels and poems, including lesser known works such as Anne of Geierstein and The Lord of the Isles, had been adapted for the stage.' Sometimes novels would reappear in unusual disguises. The Heart of Midlothian, for example, was adapted as The Lily of St Leonards and The Bride of Lammermoor as The Spectre of the Fountain.' Some novels were constantly reworked, Ivanhoe, for example, gave birth to over thirty plays and operas.' But perhaps the most famous, and certainly the most enduring, of all adaptations were those of Rob RoyMacGregor.

The vogue for stage adaptations of Scott's novels really began with Isaac Pocock's Rob Roy MacGregor, in 1818, but before that, there had been many attempts to get the formula right.' The most successful of these had been William Terry's 'Terrifications', as Scott called them, of Guy Mannering.' The Lady of the Lake had also proved a popular source, even though its first performance in Edinburgh in 1810 when it was produced as a lavish spectacle, with 'views taken from life', had been a failure, in spite of being widely advertised and eagerly looked forward to in the newspapers. 'By the time Scott died in 1832, most of his novels and poems, including lesser known works such as Anne of Geierstein and The Lord of the Isles, had been adapted for the stage.' Sometimes novels would reappear in unusual disguises. The Heart of Midlothian, for example, was adapted as The Lily of St Leonards and The Bride of Lammermoor as The Spectre of the Fountain.' Some novels were constantly reworked, Ivanhoe, for example, gave birth to over thirty plays and operas.' But perhaps the most famous, and certainly the most enduring, of all adaptations were those of Rob RoyMacGregor.

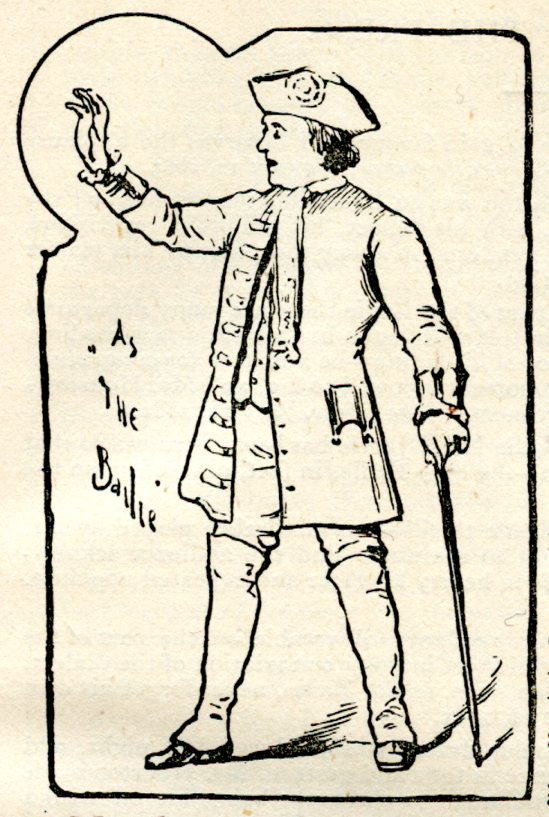

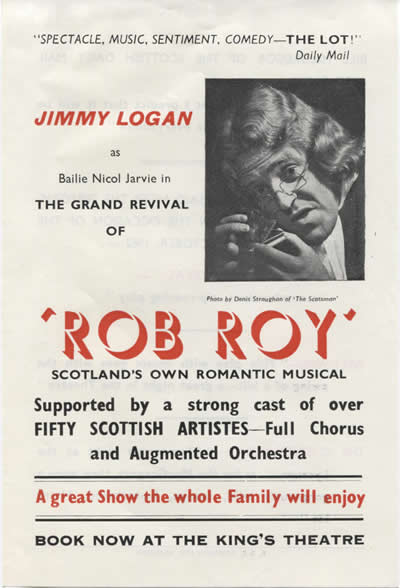

Rob Roy became the 'national drama' par excellence, mixing as it does Highlands and Lowlands, an emotional espousal of the Jacobite cause, contrasted with Bailie Nicol Jarvie's arguments on behalf of the Union, and overall sense of balance and clear view of Scottish history. 'All the adaptations kept much of the spoken Scots and preserved the memorable Scottish characters, including the 'Dougal Craitur', and Bailie Nicol Jarvie himself;' and though the Pocock adaptation, for example, only dramatises the last third of the novel in any detail, by skilful dramatic workmanship it captures the essence of the work and rigorously adheres to Scott's vision.

Rob Roy is also remembered as the play which saved the Theatre Royal Edinburgh and turned it, under the management of Mrs Henry Siddons and her brother, W H Murray, himself a practised adaptor of Scott, into the foremost theatre in Scotland.' Its final accolade came in 1822 when Rob Roy, with the famous actor William Mackay as the Bailie, was given a Royal Command performance before George IV and Scott himself. Between 1800 and 1870, and with the Theatre Royal Edinburgh at its heart and a network of theatres in every Scottish town from Dumfries to Elgin, it was possible for a Scottish actor to spend all of his or her professional life in Scotland and, with the existence of a national drama, to play a series of significant Scottish parts.' Whilst many actors chose to move to London, there too, the popularity of Sir Walter Scott meant that they could be sure of having the chance of playing some Scottish characters.' Similarly other writers who wished to put Scotland on the stage had the opportunity to do so and still see their plays widely performed.'

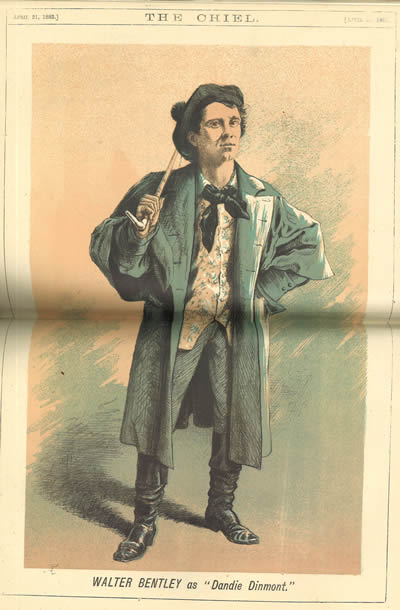

However, changing fashion and industrial innovation changed this picture. By the 1870s, thanks to the spreading railway system it became possible to tour London plays almost as soon as they had been premiered in the capital.' London became the manufacturing centre and sole exporter of most of the theatre seen across the UK.' Syndicates of theatre owners, some based in England, bought up most of the major theatres in Scotland and, rather than being the home of independent companies, these became receiving houses for endless London tours.' From the 1870s to 1909 Scotland had little or no independent theatre.' [...] But there was still a popular theatrical expression of Scotland and Scottishness. 'By the end of the nineteenth century, the only place where Scottish plays, performed in Scots and by Scottish actors, were regularly mounted was in the 'geggies', portable wood and canvas theatres which toured the small towns and poor areas of the country.' Their repertoire was Shakespeare, melodrama and the 'national drama', all three often truncated, but always sincerely played, and most important for the national drama, kept alive. 'Many of the older geggie actors were those who had performed Scottish roles at the major theatres before they became touring houses.' Younger geggy performers, like Will Fyffe, sometimes moved into music halls, performing sketches of Scottish life and characters which drew on their apprenticeship playing characters like Dandie Dinmont, the Dougal Craitur and Bailie Nicol Jarvie.

However, changing fashion and industrial innovation changed this picture. By the 1870s, thanks to the spreading railway system it became possible to tour London plays almost as soon as they had been premiered in the capital.' London became the manufacturing centre and sole exporter of most of the theatre seen across the UK.' Syndicates of theatre owners, some based in England, bought up most of the major theatres in Scotland and, rather than being the home of independent companies, these became receiving houses for endless London tours.' From the 1870s to 1909 Scotland had little or no independent theatre.' [...] But there was still a popular theatrical expression of Scotland and Scottishness. 'By the end of the nineteenth century, the only place where Scottish plays, performed in Scots and by Scottish actors, were regularly mounted was in the 'geggies', portable wood and canvas theatres which toured the small towns and poor areas of the country.' Their repertoire was Shakespeare, melodrama and the 'national drama', all three often truncated, but always sincerely played, and most important for the national drama, kept alive. 'Many of the older geggie actors were those who had performed Scottish roles at the major theatres before they became touring houses.' Younger geggy performers, like Will Fyffe, sometimes moved into music halls, performing sketches of Scottish life and characters which drew on their apprenticeship playing characters like Dandie Dinmont, the Dougal Craitur and Bailie Nicol Jarvie.

Because of a complete change in theatrical fashions, the 'national drama' written mainly for the upper-classes in Edinburgh ended up as part of the staple theatrical fare, for the working classes in the city and country.' However, the features of the 'national drama', its mixing of genre, its use of music, its direct audience involvement and above all its use of Scots, lived on in pantomime, variety and music hall and this tradition eventually fed back into the mainstream of Scottish theatre in the twentieth century.

Abridged by Paul Maloney from Alasdair Cameron, 'Scottish Drama in the Nineteenth Century' in Douglas Gifford (ed.), The History of Scottish Literature. Vol. 3 Nineteenth Century (Aberdeen University Press, 1988).

Dr Alasdair Cameron (1953-1994) was a senior lecturer in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies and a leading authority on Scottish theatre and drama. We include this essay, and its companion piece on ‘Geggies’, in memory of an inspirational teacher and colleague.

Further Reading:

Barbara Bell, 'The National Drama and the Nineteenth Century,' in Ian Brown (ed.), The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Drama (Edinburgh University Press, 2011), pp. 47-59.

___, 'The Nineteenth Century' in Bill Findlay (ed.), A History of Scottish Theatre (Polygon, 1998), pp. 137-206.

___, 'Murray to McGrath',' in Alasdair Cameron and Adrienne Scullion (eds.), Scottish Popular Theatre and Entertainment. Historical and Critical Approaches to Theatre and Film in Scotland (Glasgow University Library, 1996), pp. 1-14.

___, 'The National Drama', Theatre Research International, Vol.17, No. 2, Summer 1992, pp. 96-108.

Alasdair Cameron, 'Scottish Drama in the Nineteenth Century', in Douglas Gifford (ed.), The History of Scottish Literature: Vol. 3, Nineteenth Century, (Aberdeen University Press, 1988).

___, 'Popular Entertainment in nineteenth-century Glasgow: background and context for the Waggle o' the Kilt exhibition', in Karen Marshalsay, The Waggle o' the Kilt: Popular Entertainment and Theatre in Scotland (Glasgow University Library, 1992).

.jpg)

.jpg)