The Census

The Census

A census of the British population, providing the government with information about every man, woman and child in the country on a specified evening, has been carried out every ten years since 1801, except for 1941 when wartime conditions made it impossible. In 1841 and 1851, the General Register Office for England oversaw arrangements for taking the census in Scotland. By 1861, Scotland had its own General Register Office to assume this role, and the following section explores some of the problems encountered by the GROS staff in carrying out their first census. The new Registrar General for Scotland, William Pitt Dundas, had no prior experience of census administration and was slow to commence preparations, only just managing to get the necessary materials printed and distributed to remote areas of the country in time. Although very few householders refused to participate in the census (and those who did were soon brought into line by the threat of a fine), the enumerators appointed to distribute and collect the householders' schedules experienced other difficulties, such as householders' illiteracy and unfamiliarity with English. And these were not the only challenges with which Pitt Dundas and his Superintendent of Statistics, James Stark, were faced. On top of his regular duties, Stark was tasked with tabulating the census data and preparing the official census report for submission to Parliament. All this work had to be done manually, and as Stark's staff in the Statistical Branch of the GROS comprised only three clerks, extra help was needed. Pitt Dundas initially received Treasury permission to employ a total of six temporary staff for the census, including junior clerks, superior clerks and two overseers or superintendents, with the option of engaging an additional six clerks later on. As in England, the candidates for these positions had to pass Civil Service examinations in handwriting, orthography, elementary arithmetic and copying before they could be appointed. Delays occurred because some of the first six men nomined by Pitt Dundas failed the examination, meaning that new candidates had to be found and sent up for examination. The twelve-man census staff was not in full working order until August 1861, and then still more clerks were required, Pitt Dundas requesting another eight in September 1861, and a further four in April 1862. Thanks to these additional pairs of hands, work on the census of 1861 was finally completed on 10 February 1864.

The Enumerators

The census was taken on the evening of Sunday 7 April, 1861. Some weeks earlier, Scotland's 1001 registrars of births, deaths and marriages had been ordered to split their respective parishes into small enumeration divisions, and appoint an enumerator for every division. The enumerators' job was to call at each dwelling, give a blank census schedule to every householder, and remind them to fill in the requisite information on census night; to collect the completed schedules on the morning of 8 April and, if any remained empty, to fill them in on the householders' behalf; to transcribe the contents of all the completed schedules into an enumeration book; and finally, to prepare summaries of the total numbers of houses, persons in houses, persons not in houses, and males and females temporarily absent or present in their division. The instructions issued to registrars explained that:

'The Enumerator, in order to fulfil his duties properly, must be a person of intelligence and activity: he must read and write well, and have some knowledge of arithmetic: he must not be infirm, nor of such weak health as may render him unable to undergo the requisite exertion: he should not be younger than eighteen years of age, nor older than sixty-five: he must be temperate, orderly, and respectable, and be such a person as is likely to conduct himself with strict propriety, and to deserve the good-will of the inhabitants of his District. He should also be well acquainted with the District in which he will be required to act, and it will be an additional recommendation if his occupations have been in any degree of a similar kind.'

But it proved very difficult to recruit enumerators who answered this description. In rural areas, suitably educated men were often in short supply. The fee offered, £1 10s, was also substantially less than the enumerators had earned at the previous census of 1851, prompting many experienced men to refuse the job. As a result, Pitt Dundas was deluged with correspondence from anxious registrars who were struggling to secure good candidates. Several registrars, particularly in the Highlands and Islands, were forced to recruit men from outside their own parish boundaries, and others served as enumerators themselves to make up the numbers. Although the full complement of 8,075 enumerators was eventually secured, they were of varying abilities and occupational backgrounds, ranging from accountants and surveyors in Perth, to fish curers and foresters in Uig. The published census report makes no mention of problems in procuring sufficient enumerators, or of the fact that many were not of the desired calibre; but anyone using the census data for research needs to be aware of this, as it must have affected the quality and accuracy of the information gathered.

In the weeks approaching the census night, all registrars were obliged to check that the enumerators had read their instructions and knew what was expected of them. As we shall see, however, many of the registrars were mistaken or unclear about how certain columns of the householders' schedule should be completed, so they may not have advised their enumerators correctly.

Children Attending School

The Scottish census schedule for 1861 required each householder to state the number of children under his or her roof, aged from 5 to 15 inclusive, who had attended school during the week preceding 7 April; but people's understanding of the term 'school' varied considerably. Several registrars asked Pitt Dundas whether children taught at home by governesses should be considered as attending school, and were told that they should not. The registrar of Sanday asked whether children who attended day schools should be counted, or only those at boarding establishments, and was advised to include both groups. Another confusing point, and one on which Pitt Dundas actually changed his mind, was whether or not to count children attending only Sabbath schools for religious instruction. On 28 March, Pitt Dundas assured the registrar of Lesmahagow that such children should be included. Yet a few days later, the registrar of Hamilton warned that if this course were followed, 'a most erroneous result will be obtained as to the real state of education in Scotland, as a very small proportion indeed of Sabbath School Children are attending School during the week.' He urged Pitt Dundas to reconsider the matter, 'so that we may be able to guide our enumerators properly.' Soon afterwards, the registrars of Hamilton and Lesmahagow both received letters indicating that 'the Registrar General has come to the conclusion that children attending a Sabbath School ought not to be taken into account along with other school children in the last Column of the Householders Schedule.' But the other 999 registrars were not officially informed of this decision. Consequently, many enumerators and householders would have followed the old instructions, or relied upon their own interpretations of the term 'school', when completing the schedules.

In rural and island parishes, the customary April school holidays to allow children to assist with agricultural tasks posed another quandary for registrars and enumerators. The registrar of Unst told Pitt Dundas that:

'at this season, most of the children who have attended School during winter, leave for the labours of the field. In the five schools in Unst perhaps there will not be a single Scholar on 6th April. How is this to be met? Will it answer the purpose intended to give the number of Scholars who have attended School during the winter quarter between the ages specified in the Schedule?'

The Registrar General's Secretary, George Seton, replied that only those children who physically attended school during the week preceding 7 April should be entered. Yet when the registrar of Yarrow explained that the parish school would be on holiday from 5-9 April and asked if the number of scholars present on 4 April should be entered instead, Pitt Dundas agreed! Such inconsistency must have affected the census figures. The reason for including this column in the schedule had been to discover the number of children who were 'receiving instruction in the ordinary branches of education'; but, as the published census report admitted, the wording of the column served to exclude children who were absent for more than a week from sickness, who could not attend school because it was closed for the holidays, or who were educated privately at home. Anyone using the 1861 census to research the history of education in a particular locality or to track levels of school attendance over time should therefore treat the recorded figures with caution, and always seek corroboration from other sources.

Number of Windowed Rooms

To satisfy the desire of social and sanitary reformers for statistics showing the number of persons to each room, and the extent of ventilation in Scottish homes, the 1861 census schedule required each householder to state the number of windowed rooms in their dwelling. There was much confusion about how to reckon this figure, and some people probably wrote down the total number of windows, instead of the number of rooms with windows. Several registrars queried the very definition of a window, particularly where Highland cottages were concerned. The registrar of Kirkton, near Thurso, wrote to Pitt Dundas:

'In this District there are many of the Straw Thatched Houses of the small Tenants & others, lighted only by a small sky light with only one pane of glass, and many others have only a very small window-frame in the wall, without any glass, but fitted with a Board or Boards Opening on hinges. Are these to be reckoned as windows in the sense of the Act?'

The official response to these and similar queries was that an aperture had to be glazed to qualify as a window, and not, as the Registrar General emphasized, 'a mere hole in the wall.'

(Image: Highland cottage, by permission of Glasgow University Library, Department of Special Collections.)

(Image: Highland cottage, by permission of Glasgow University Library, Department of Special Collections.)

Doubts about what constituted a room prompted a further flurry of queries. Did a passage or lobby count? What about pantries, kitchens and similar apartments used for purposes other than sleeping or sitting? And did an apartment require a fireplace to qualify as a room? The official replies to these questions were no, yes, and no respectively. Some of the Highland registrars also enquired whether the characteristic 'but and ben' cottage, with one of its two apartments forming the family dwelling and the other the husband's workshop, should be entered as having one, or two windowed rooms. They were told to consider these as having only one room, because the workshop was used solely for the purposes of trade; but registrars who did not write to the Registrar General for clarification could easily have reached the opposite conclusion and advised their enumerators and householders to put down two windowed rooms. Despite the confusion, the GROS did not issue any general notice of clarification to all the registrars. No wonder, then, that when the Sheriff Clerk at Lochmaddy cast his eye over the completed census documents for that locality, he found:

'the great majority of Enumerators have put down these apartments . . . as rooms having windows, while others have not thought these openings deserving the name of windows and have not, in a whole division, entered one house as having a window.'

Language and Literacy

In the Highlands and Islands, the fact that most people spoke only Gaelic and could neither write nor read English obliged the enumerators to fill in almost every householder's schedule themselves. The Registrar General for England and Wales had provided a Welsh translation of the schedule for every census since 1841, and in 1861 it was suggested that the Scottish Registrar General might supply a similar translation for native Gaelic speakers; but for reasons of time, economy and convenience, Pitt Dundas decided against this.

If native Gaelic speakers could not comprehend the schedule, the enumerator had to obtain the necessary particulars from them verbally and write them in himself. This meant firstly translating the English questions into Gaelic, then the Gaelic responses into English. Unless the enumerator possessed sufficient linguistic abilities and interpretational skills, misconceptions might easily occur and unintentional errors creep into the schedule, perhaps never to be picked up. As we have seen, the registrars struggled to procure suitably qualified enumerators and not all of them would have been expert in both languages. The registrars themselves, whose regular duty involved translating and recording in English the details of any births, deaths and marriages reported to them in Gaelic, ought to have been well practised in this, and their personal knowledge of parishioners' social and familial circumstances ought also to have alerted them to any obvious misconceptions arising from anglicization. However, some of them were not renowned for their own accuracy and it is unlikely that every registrar checked his enumerators' work scrupulously. Users of the census, especially if searching for a particular ancestor, should remember that householders' illiteracy and/or unfamiliarity with English could affect the appearance of the returns, and that these householders had to rely on enumerators, whose handwriting, spelling and comprehension were not always much better than their own, to convey the necessary information.

Omissions From the Census

Particularly in the large cities of Dundee, Glasgow and Edinburgh, enumerators were sometimes guilty of omitting households from the census returns. Although the registrars were supposed to check for any such omissions, these sometimes went undetected until the householders concerned complained that they had been left out. The Glasgow Herald of 9 April published a letter from one indignant gentleman, enquiring:

'whether . . . the officials employed in distributing the schedules were furnished with any list of the householders, ratepayers, &c., or were they just left to grope their way through every domicile they could find? I take the liberty of putting this query principally because I, occupying with my family a house of six apartments, have never been favoured with a visit from any such official, or seen such a thing as a schedule at all. It is not at all likely that mine is a solitary case - (indeed, I have heard of several others) - and were there only one such in every street, it would materially affect the "truth of the whole."'

Another letter, printed in the Scotsman, insisted that the Edinburgh census had been 'completely bungled', and that many households were missed out because the enumerators had been 'very much underpaid, and they either did not do their duty at all or they did it ill'.

Leaving aside groups such as vagrants and travellers, who were always difficult to enumerate, such comments beg the question of how many other householders and their families may have been left out of the 1861 census. For the lower classes, filling in the householders' schedule (or dictating the answers to an enumerator) must have seemed a troublesome task for no reward, and, rather than drawing attention to the fact, they might simply have kept quiet if they never received a schedule. It is essential that users of the census, especially those interested in the growth and development of particular towns and parishes, or those puzzled about missing ancestors who they had expected to find, should understand this, as the published census reports make no reference to omissions at all, and do not tell the whole story.

Subsequent Censuses

Having negotiated a steep learning curve during the census of 1861, Pitt Dundas and Stark were better prepared for the next one in 1871. The Census Office was also more adequately staffed, with 24 clerks from the outset, but production of the census report was delayed once again, Stark being by this time in poor health and absent from the office on several occasions. In March 1874, Pitt Dundas had to inform the Treasury that the report would not be ready until at least May, explaining that it 'has no doubt been much retarded by Dr Stark's repeated and prolonged illnesses'. This placed Pitt Dundas in a difficult position with the Treasury, and tested his already strained relationship with Stark to the limit - after failing to persuade him to resign on grounds of ill health, he finally forced Stark to do so.

As we would expect, the information requested in the householders' schedule expanded and changed with each census - in 1921, for example, the column for marital status included an option for 'Divorced' for the first time. Each successive census also brought its own problems and challenges for the GROS, such as the use of Hollerith machines to speed up the process of calculation.

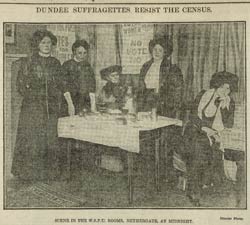

(Image: 'Dundee Suffragettes Resist the Census,' by permission of Dundee Central Library.)

(Image: 'Dundee Suffragettes Resist the Census,' by permission of Dundee Central Library.)

When the 1911 census was being taken, suffragettes in many parts of Britain staged protests, arguing that since they were not recognized as citizens and were not allowed to vote, they had no duty to be counted in the national census. In London, a large suffragette procession marched through the streets, but in Dundee (where the suffragettes probably wisely decided to protest indoors), several gathered in their offices and sat there through the night to avoid being counted at their homes. The illustration shows them engaged in their 'stopout' protest. And in 1941, Britain was at war and the census was suspended altogether.