Launching a tool to help non-scientists with Understanding Health Research: one month on

Published: 19 September 2016

A month ago, we launched Understanding Health Research, an online resource designed to help guide non-scientists through the process of understanding and appraising a piece of published health research.

Going live

A month ago, we launched Understanding Health Research, an online resource designed to help guide non-scientists through the process of understanding and appraising a piece of published health research.

The launch gave us an opportunity to discuss the importance of empowering people to engage with health science. It’s been great to have others join the conversation on social media and talk about what Understanding Health Research can do, and to gain the support of academics, the voluntary sector and the NHS. Our launch campaign, designed and implemented in collaboration with Sense about Science, succeeded in driving users to the site, and more, importantly, generated much useful feedback.

Understanding Health Research is now live and available to anyone, but we know it’s not sufficient to leave people to discover it for themselves, so we have begun to promote the tool through a series of introductory workshops for students and others. These workshops cover many of the key concepts addressed in the tool, and we will be adapting them for different audiences as we go along.

One size fits all?

We feel that there are many situations where Understanding Health Research can be useful, and we’re determined to ensure that it meets the full potential it offers.

A member of the public may wonder whether a health claim they read in the newspaper is supported by evidence. A patient may wish to understand the published evidence about potential treatments for a health condition they have been diagnosed with. A journalist reporting on new piece of research may wish to check that they are representing the science fairly. A student reviewing scientific literature for the first time may be looking for reassurance about how to critically appraise research. Or an early-career researcher may need guidance through the process of reviewing academic literature that uses methods they are not familiar with.

In all of these cases, Understanding Health Research can help users to ask the right questions of a research study and understand what the answers to those questions mean.

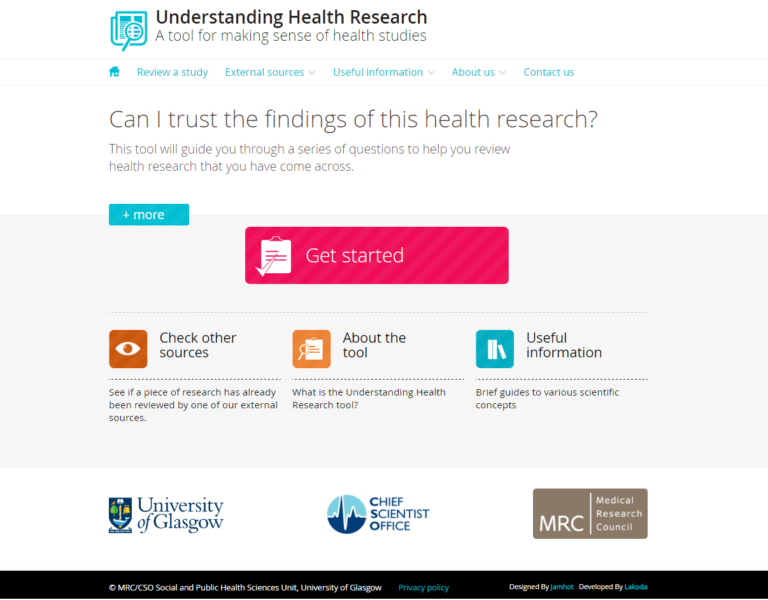

Understanding Health Research homepage

Critically appraising the evidence behind the news

To explain what Understanding Health Research can do, consider this piece of research, which was published in the Journal of Health Psychology at the same time that our new tool went live in August. This research was picked up by major UK newspapers: The Independent, The Daily Mail and The Telegraph, each reporting that the research showed that “Laziness is a sign of intelligence”.

Readers wondering to what extent that claim is supported by evidence can access the original paper behind the stories, but academic papers can be unwelcoming to people who aren’t familiar with them. This is where Understanding Health Research can help.

So, what would someone find if they put that research through Understanding Health Research? They would find many interesting and reassuring things: the paper was peer reviewed; the research was neither carried out nor funded by organisations likely to have a vested interest in the results; and the study had ethical approval. The user would identify that this research had a clear research question, which is an essential element of a useful research paper, and in examining the research question, the reader might begin to wonder if the newspaper headlines would be supported by the evidence. They would go on to identify that the research uses an observational study design, and consider the strengths and weaknesses of that type of design.

The next series of questions covers key issues relevant to the research design, like the characteristics of the research participants, the process of data collection and the effects of confounding factors. Then, the user would engage with the essential issues of whether the paper answers the research question, whether the conclusions were valid, and whether the authors acknowledged any competing interests. Crucially, the tool would encourage the user to think about whether the research fits their own circumstances, and would stress the value of systematic reviews over individual studies.

A final judgement?

The final part of Understanding Health Research is a summary page listing each answer the user has given to help them reach a final conclusion. Most studies have some merit, and every study has some limitations, but our aim is for the tool to empower people to engage with the nuances of health science, to better understand why individual research studies rarely give us the concrete conclusions that we often want and that newspaper headlines often promise.

So taking our example here, what might our user conclude? They would see that this research paper was published in a peer-reviewed academic journal, and that it clearly describes the aims, methods and findings of the research. The research has limitations, but, crucially, these limitations are explained by the authors in the paper, which allows readers to consider how those limitations could have affected the findings. These limitations do not mean the research is not useful, but they can help a critical reader understand how further research might paint a fuller picture.

And what of the $64,000 question of whether the research paper finds that “Laziness is a sign of intelligence”? After reviewing the paper with our tool, our user might conclude that the headline does not tell the full story. What the research does tell us is that, in a group of predominantly female university students in the US engaged in coursework, people who preferred thinking more were less physically active during the week in which their activity was measured. The research concludes that “need for cognition” and physical activity may be correlated, but cannot tell us whether one of those things influences the other and, if so, direction of the causal relationship.

Thinking critically

Many health claims in the media have some truth to them, and many are based on sound research evidence, supported by well-explained press releases and written by skilled journalists, but often headlines make research evidence sound much more definitive or exciting than it is, with important caveats often omitted or causal relationships sometimes implied without the evidence to support them.

Whether we are assessing health claims in newspapers, online or in scientific papers, it’s vital that we all ask the right critical questions about them. There is no one-size-fits-all fix for health science literacy, but we believe that our tool complements the range of existing tools that help empower anyone to engage critically with health evidence. In the month since launch we’ve seen such a positive, welcome response from the academic community and the public as we continue to promote the tool, and hope that many more people will find it helpful.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this blog are those of the authors.

This research was funded by a grant from the Medical Research Council Public Health Science Research Network. The MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit is funded by the Medical Research Council and the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office.

First published: 19 September 2016