Eliminating rabies

At the University of Glasgow, we are at the forefront of research into rabies elimination.

Rabies is a horrifying and deadly viral disease that kills tens of thousands of people every year in low- and middle-income countries, despite being 100 per cent preventable.

The virus is transmitted through the saliva or tissues from an infected mammal to another mammal. Most human cases of rabies are caused by a bite or scratch from an infected dog, though rabies also exists in other animal reservoirs including bats, raccoons, skunks, foxes and coyotes.

Unless a regimen of vaccines are administered, about 20 per cent of bite victims go on to develop rabies, but the disease can only be diagnosed once symptoms develop. The incubation period is usually between two and twelve weeks and it is a disease with a 100 per cent fatality rate.

Rabies affects the nervous system, and the symptoms are highly distressing for both the victim and those caring for them. Initially, pain and stiffness start at the site of the wound, followed by fever, delirium, aggression and strange and uncontrollable vocalisations. Hydrophobia (fear of water) can also be a symptom. There is no effective treatment and palliative care is the only recommendation. Death occurs between two and ten days after the first symptoms appear.

Rabies transmitted by dogs used to be found almost all over the world, however it is has been eliminated from dog populations in developed countries. Most rabies deaths today are in Africa and Asia where rabies is still prevalent in dogs. Tragically, many of the victims of rabies are children from poor, rural and often marginalised communities where there is little access to healthcare. Rabies therefore exemplifies both global and local health inequalities.

Though rabies cannot be completely eradicated as a virus, rabies in humans can be eliminated. This is achieved through dog vaccination campaigns which are supplemented with a programme of post-bite vaccinations for people, known as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

For PEP to be effective, the programme of vaccinations must be delivered promptly following the bite of a rabid animal. As these vaccines are very expensive and usually only available in major cities, it often renders them inaccessible to the rural poor who are most vulnerable to the disease.

Rabies research at Glasgow

Scientists at Glasgow have been conducting research in Tanzania for almost 20 years to answer fundamental questions such as: what is the scale of the rabies problem? how does the virus circulate? and what are the most effective control strategies?

Key Glasgow scientists carrying out this research are Professor Katie Hampson, Professor Sarah Cleaveland and Dr Tiziana Lembo.

Research led by Professor Hampson has included a global study on the burden of rabies in 2015, where epidemiological and surveillance data was used to estimate that 59,000 people a year die from canine rabies, with the highest death rates being in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic losses from the disease were calculated to be 8.6 billion US dollars annually.

The researchers have highlighted that the most straightforward approach to eliminating rabies is through the mass vaccination of domestic dogs. If 70 per cent of dogs are vaccinated during sustained vaccination campaigns, then the rabies virus that causes 99 per cent of human rabies deaths around the world today would disappear completely.

The researchers have highlighted that the most straightforward approach to eliminating rabies is through the mass vaccination of domestic dogs. If 70 per cent of dogs are vaccinated during sustained vaccination campaigns, then the rabies virus that causes 99 per cent of human rabies deaths around the world today would disappear completely.

This approach is both a practical and cost-effective means of reducing human rabies deaths as through curbing the rabies virus in the source, the problem is alleviated in humans.

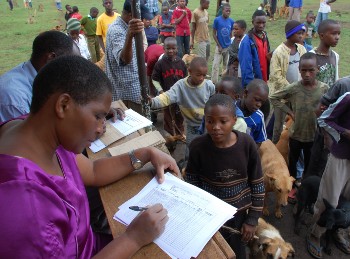

Their research has also uncovered that most dogs in African villages, though they may roam freely, are in fact domestic pets rather than strays. Subsequently, by setting up dog vaccination clinics where owners are encouraged to bring their dogs, the virus can be gradually eliminated.

Gavi investment

In 2018, a study led by Katie Hampson highlighted the life-saving potential of investment in post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

Current PEP use in the poorest countries around the world saves approximately 56,000 lives annually, however it has the potential to save many more. But high costs and limited access and supply means availability of PEP remains poor in many of these rabies-endemic countries.

Professor Hampson’s research used epidemiological and economic modelling to compare potential investment by Gavi to the status quo. They predicted that, under the current status quo, more than one million deaths will occur in the 67 rabies-endemic countries studied from 2020-2035. However, if there was investment in PEP, and access to the vaccines for patients was expanded and provided free of charge, it’s estimated that an additional 489,000 deaths could be prevented in the same time period.

Professor Hampson’s research used epidemiological and economic modelling to compare potential investment by Gavi to the status quo. They predicted that, under the current status quo, more than one million deaths will occur in the 67 rabies-endemic countries studied from 2020-2035. However, if there was investment in PEP, and access to the vaccines for patients was expanded and provided free of charge, it’s estimated that an additional 489,000 deaths could be prevented in the same time period.

Central to this is the idea that vaccines are free: “We made the assumption that if Gavi invested, they would ensure that patients don’t have to pay for the vaccine.” says Professor Hampson. “We know that the cost of the vaccine is currently a huge obstacle; some patients don’t seek care because they know it’s too expensive, or they do seek care but they’re critically delayed in getting to the hospital because they have to raise the money to pay for it.”

The researchers also examined the available vaccine regimens to determine which would be most effective for potential investment. Professor Hampson explains: “We looked at the different regimens the WHO agree are safe and effective and worked out which of those was actually the most cost-effective, so used the least vaccine but saved the most lives.” A practical and affordable one-week PEP regimen was subsequently recommended in the study.

The evidence amassed in the study was compelling enough to influence Gavi in their decision to invest in PEP in their 2021-2025 strategy, with countries able to apply for the new Gavi support from 2021 onwards.

Scaling up mass dog vaccination

Katie Hampson and colleagues are now trialling a number of dog vaccination initiatives across different parts of East Africa to establish what works operationally before they can be rapidly scaled up nationally and across trans-national boundaries.

This includes graduate student Ahmed Lugelo who is running a trial across 400 villages in north-west Tanzania, trialling two different types of dog vaccination strategy to establish which is most cost-effective and feasible to roll out to other communities.

In Kenya, Dr Thumbi Mwangi is mobilising similar campaigns with the government as well as organising regional strategy meetings to coordinate these efforts across national boundaries in East Africa.

“We’re trying to cost up and evaluate these pilot vaccination strategies so that we can apply the lessons we learn from them to the scaling up of dog vaccinations across the entire country.” says Professor Hampson. “In general, doing these large-scale campaigns is not something that has been routinely part of national government strategies, so there’s a combination of advocacy, demonstration of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness that needs to be achieved.”

“We’re trying to cost up and evaluate these pilot vaccination strategies so that we can apply the lessons we learn from them to the scaling up of dog vaccinations across the entire country.” says Professor Hampson. “In general, doing these large-scale campaigns is not something that has been routinely part of national government strategies, so there’s a combination of advocacy, demonstration of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness that needs to be achieved.”

Surveillance of the disease is also a key part of the team’s research efforts: “We need to demonstrate what the impacts of the dog vaccinations are, monitor if there’s places where dog vaccinations are not being done well enough, or where dog vaccinations need to be put in place as a matter of urgency because there are outbreaks going on” explains Professor Hampson.

Surveillance technology

Surveillance of rabies in Tanzania has been greatly aided by a mobile phone app developed by Katie Hampson’s team, to closely monitor rabies in animal and human populations in Tanzania.

An app used as part of this mHealth approach was developed by Zac Mtema and is used by frontline health and veterinary workers to track rabies across large parts of the country. It enables them to report bite victims, as well as all human and animal rabies vaccinations. The surveillance data is held in a central database that can be accessed by government officials and researchers to help monitor the virus and coordinate vaccination campaigns.

An app used as part of this mHealth approach was developed by Zac Mtema and is used by frontline health and veterinary workers to track rabies across large parts of the country. It enables them to report bite victims, as well as all human and animal rabies vaccinations. The surveillance data is held in a central database that can be accessed by government officials and researchers to help monitor the virus and coordinate vaccination campaigns.

The app has been extended further in partnership with PhD student Kennedy Lushasi and is now used for a new type of surveillance called ‘integrated bite case management’, which supports collaboration between health and veterinary workers. When a patient presents to a clinic, health workers carry out a risk assessment to assess whether the patient is at high risk of having been exposed to rabies. If they have, it automatically prompts livestock field officers to investigate potential instances of animal rabies.

These risk assessments also provide useful data to help understand the impact of PEP, as Professor Hampson states: “It’s a good way of uncovering whether people presenting to a clinic are really presenting because of a true exposure to rabies. This helps us identify how many lives are being saved, or would be saved, by PEP being delivered rapidly to stop them developing rabies. This will be really useful information to help inform any Gavi investment and for understanding progress towards the 2030 target for rabies elimination.”

Sequencing the virus

Researchers Dr Kirstyn Bunker and Gurdeep Kour have been working on sequencing the various rabies viruses circulating in East Africa. This is another form of surveillance that helps the team trace the virus and understand how the disease is spreading.

As dog vaccinations are scaled up and rabies starts to decline, knowledge about the diversity of viruses that are circulating will help to uncover any trans-boundary spread:

“We know the viruses that circulate in Kenya, and we know the viruses that circulate in Tanzania,” says Professor Hampson. “So, as we hopefully begin to get rid of both, we can see where new cases are coming from, and if they are undetected local transmission or introductions from other regions.”

New insights into the persistence of the pathogen

In 2022, new findings from Katie Hampson and her international team of researchers revealed why rabies remains endemic in Africa despite overall low virus prevalence (only 0.15% of the dog population is infected annually) and attempts to combat the pathogen.

This persistent circulation of rabies at very low prevalence in largely unvaccinated domestic dog populations had been an enduring scientific enigma.

To understand the virus dynamics, researchers tracked rabies transmissions, dog population densities, disease incidence and vaccination campaigns in more than 50,000 domestic dogs in Serengeti, Tanzania from 2002 until 2016.

The researchers discovered that the mobility and behaviour of individual rabid dogs was a key factor in the spread of the virus. A small proportion of infected dogs act as ‘super spreaders’ travelling more than 10km to bite other animals. This brings new virus lineages to different communities and so seeds new outbreaks.

Professor Hampson says: “The virus uses a clever strategy for low level persistence, which makes its dynamics harder to both detect and predict. But these new mechanistic insights also show why scaling up dog vaccination is so necessary.”

According to the findings, the processes that underpin the persistence and prevalence of rabies operate on scales much smaller than those typically modelled for the disease. The enduring circulation of rabies is often down to the behaviour of a few individual infected dogs.

Over the 14 years, the researchers were able to pinpoint hundreds of introductions from neighbouring villages that were able to sustain circulation across the region. The variability in rabid dog biting behaviour means that most introductions do not take off, but some of the outbreaks that do last for years. This co-circulation of different rabies virus lineages underpins the virus persistence.

Benefits of a One Health approach

Rabies is a zoonotic disease that spans human and animal health therefore a One Health approach is essential to effectively combatting the disease. Professor Hampson stresses the ongoing positive impact from strengthening linkages between the human and animal health sectors:

“Rabies is a clear example where intervening in the animal population has benefits for public health. But, more widely, good communication and collaboration between the animal and human health sectors can be extremely beneficial for other diseases such as anthrax, brucellosis and leptospirosis, which all have major public health impacts in Tanzania and other African countries.”

“Building strong partnerships between sectors is crucial to tackling these diseases. So if there’s an outbreak of disease in the animal population, the human health sector can be prepared. Conversely, if the human health sector is seeing patients, it’s only through good communication with the animal sector that an intervention can be implemented to stop the disease at its source.”

Impact of research

Katie Hampson and her team’s world-leading research has influenced policy on both a national and global level. They have advised national governments on large-scale rabies surveillance and control programmes, and their research has prompted global agencies, including the World Health Organization, to advocate and invest in strategies which should lead to the global elimination of rabies by 2030.

Katie Hampson is funded by Wellcome.

Selected publications

- 'Rabies shows how scale of transmission can enable acute infections to persist at low prevalence', Science

- 'The potential effect of improved provision of rabies post-exposure prophylaxis in Gavi-eligible countries: a modelling study', Lancet Infectious Diseases

- 'Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies', PLOS Neglected Diseases

- 'Toward Elimination of Dog-Mediated Human Rabies: Experiences from Implementing a Large-scale Demonstration Project in Southern Tanzania', Frontiers in Veterinary Science

- 'Mobile Phones As Surveillance Tools: Implementing and Evaluating a Large-Scale Intersectoral Surveillance System for Rabies in Tanzania', PLOS Medicine

- 'Implementing Pasteur's vision for rabies elimination', Science