William Hunter and the Anatomy of the Modern Museum

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS

For the first time in 150 years, visitors will be able to see the scale and quality of Hunter's collections all in one place, reuniting paintings, ethnographic objects, anatomical and natural history preparations and items from Hunter's library and great coin collections. There are more than 400 items on display and a small selection can be viewed below.

NEXT

Events

BACK TO

Dr William Hunter

Allan Ramsay (Scottish, 1713–1784)

Allan Ramsay (Scottish, 1713–1784)

William Hunter

c. 1764–65

Oil on canvas

When Allan Ramsay painted William Hunter’s portrait in the mid-1760s, the two friends, both at the height of their professions, were increasingly torn between the pursuit of their chosen careers and engagement with other interests. Ramsay had a strong inclination toward the literary and the antiquarian, as indicated by the growing list of his published writings, all represented in Hunter’s library, whereas Hunter’s was a determination to create a national school of anatomy supported by a multidisciplinary museum, and to expand his scientific inquiries beyond human anatomy alone. The existence of a preparatory drawing for Hunter’s portrait, kept in the National Galleries of Scotland, suggests its composition was the result of a dialogue between the painter and sitter. Starting with a three-quarter- length format, it was reduced to a seated bust, reflecting a move toward a private, intimate likeness rather than a celebration of the sitter’s public achievements. The result, the earliest known portrait of Hunter, is among Ramsay’s mature masterpieces and belongs to his select group of probing depictions of influential members of London’s most brilliant Enlightenment salons.

Stater of Lachares

Stater of Lachares

Athenian

296–94 BCE

Gold

One of The Hunterian’s great treasures is the 'little gold coin of Athens'. Though most Athenian coinage is of silver or bronze, gold was issued on rare occasions, usually associated with war. This stater, as with most of the currency of the city, bears the head of its patron deity, Athena, on its obverse, and on the reverse, her special symbol, the owl, as goddess of wisdom and the night. The three Greek letters indicate that the coin is 'of the Athenians'. It was struck by the tyrant Lachares, who ruled from 296 to 294 BCE, during the great siege of Athens by Demetrius Poliorcetes of Macedon. Short of money, Lachares stripped the Acropolis, including the famed statue of Athena, of its gold coverings to convert this into coins. Possibly made from the statue, this was the only specimen known in the 18th century and belonged to George III, who presented it to William Hunter.

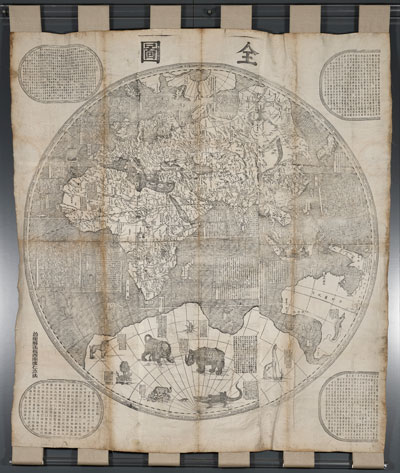

Ferdinand Verbiest (Flemish, 1623–1688)

Ferdinand Verbiest (Flemish, 1623–1688)

Kunyu Quantu

1674

Woodblock print on paper laid down on cloth, in four parts

The Kunyu Quantu, or map of the whole world, was one element of a larger project to document both human and physical geography. Designed for Kangxi, the second Qing Emperor of China (reigned 1661–1722), by Ferdinand Verbiest, a Flemish Jesuit who served as the director of the Imperial Observatory, it shows the use of European cartography as part of the Emperor’s programme to consolidate dynastic power. Eight texts enclosed in cartouches provide information concerning natural phenomena, such as eclipses and earthquakes, and the inhabitants, customs, climate, and land forms of particular nations and regions. Real and imaginary animals, including sea creatures, are depicted in a manner following the iconography of European natural histories, most notably the Historia animalium (1551–58 and 1587) published in Zurich by Conrad Gessner (1516–1565).

Casts of the Gravid Uterus

Casts of the Gravid Uterus

Over a period of more than twenty years beginning in 1750, William Hunter pursued the goal of mapping the anatomy of the human gravid uterus by dissecting thirteen subjects—bodies of women who died during various stages of pregnancy. During the dissections, information was preserved in several media: polychrome plaster casts, drawings, and anatomical preparations. The casts and preparations were used for teaching and documentation of research. Finished drawings were later translated into thirty-four engravings, initially printed as proofs, and subsequently published in Hunter’s HUNTER’S 'FIRST SUBJECT' (1750–52) First Phase of Dissection: Plaster Cast and Plates II and III of The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, the Gravid Uterus anatomical atlas with accompanying Latin and English text: Anatomia uteri humani gravidi tabulis illustrata / The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures (1774).

Maori, South Island, New Zealand, Polynesia

Cloak

18th century

Flax and feathers

Following their migration from tropical central Polynesia to a temperate environment, Maori responded by creating garments from harakeke, or New Zealand flax (Phormium tenax), varieties of which grew widely in their new home. The supple fibre was finely woven, and many cloaks featured a taniko border made up of dyed fabric forming linear or geometric motifs. For Maori, feathers, especially rarer and red feathers, were expressions of spiritual power, associated with birds, flight, and deities. This remarkable cloak features both a complex set of triangular and diamond-shaped motifs along the lower border and twelve rows of feather clusters, alternated so as to form a sort of chequer-board of high-value plumage, with, also unusually, tips pointing upward toward the head of the wearer. The structure, provenance, and symbolic associations of this cloak demand fuller investigation, but there can be no doubt that this was a truly exceptional garment, presumably made for a person of great status and mana (spiritual power).

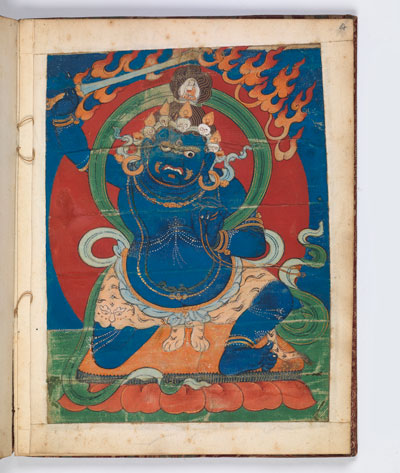

Idolum Tangutanum

Tibetan

17th? century, in an 18th-century Russian manuscript volume

Paint on cloth, pasteboards, and paper

This painting on cloth is a thangka, a Tibetan religious image, which was taken from the ruined Buddhist monastery near Semipalatinsk in present-day Kazakhstan. It belonged to Theophilus Siegfried Bayer (1694– 1738), professor at the St Petersburg Academy of Sciences. A particularly prized object of Bayer’s, the painting was known to its owner as his Idolum Tangutanum, or Tibetan idol. It depicts the Tantric meditational deity Candamahārosana—the wrathful aspect of Aksobhya—squatting on a cushion that rests on seven lotus petals. The deity wears a tiger skin as a loin-cloth; a green scarf forms an aureole above his head; and from his neck hang a long gold necklace and a twisted green snake. In his left hand he holds a golden noose, while in his right is a sword, round which play tongues of fire. His head is crowned with a chaplet of skulls, and his hair, drawn into a topknot, contains the figure of Aksobhya, who adopts the 'earth-touching' mudra, or hand gesture. On the verso of the picture are inscriptions in Tibetan, one of which invokes the deity.

William Hunter and assistants

Severe lateral curvature of the spine

1746–83

Human spine and wooden base

This specimen is a very deformed vertebral column and ribcage from an adult human. Normal curvature of the thoracic spine is exaggerated (kyphosis), and there is also a marked side-to- side curvature (scoliosis). In life, the subject would have been stooped and also may have suffered breathing difficulties. The cause of the condition is unknown for this individual as no medical notes survive. Notes on individual patients are sparse. Modern diagnosis would consider rickets or osteoporosis. William Hunter had an extensive collection of bone pathology specimens. Bones were prepared by maceration (soaking or boiling in water) and then dried. Only a few special specimens were mounted in glass jars; most were stored in drawers.

Rhetenor blue morpho butterfly

Morpho rhetenor Cramer, 1775

Suriname

To obtain exotic insect specimens in the 18th century was hazardous. To convey the specimens intact from the collection site, across land and sea, to Britain presented further challenges. Wings, legs, and antennae are particularly vulnerable in transit, and damaged specimens are not as collectable, or useful for display or scientific investigation. Consequently, it is unsurprising that repairs have been identified on numerous specimens in Hunter’s cabinet. One of the four Morpho rhetenor specimens has replacement antennae fashioned from trimmed feather quills. This one appears to be the only one with an artificial body. A new thorax and abdomen have been sculpted, coloured, and attached to the original wings and head. The materials used in the repair are not yet established, but possibly include wood or cork. The left wing bears a very clear thumb print that was most likely left by the individual who set or repaired the butterfly.

Thorny oyster shell with Noah’s Ark shell

Spondylus gaederopus Linnaeus, 1758

Mediterranean

William Hunter’s exceptional shell collection was acquired from a variety of sources, though details of both gifts and purchases are sparse. There are two of these natural concretions in his collection. Thorny oysters cement themselves to rocks, and these specimens have been adventitiously settled on by other marine animals: coral, Serpula tube-worms, and another bivalve, the strikingly marked Noah’s Ark shell.

Copper, intergrown with white quartz

Probably Cornwall

Around 1765, Elizabeth, Lady St Aubyn, sent a collection of mineral specimens from Cornwall to London as a gift to William Hunter. This specimen is very likely from Lady St Aubyn’s donation. Copper usually occurs chemically combined with other elements, but some Cornish mines contained large quantities of naturally occurring pure copper metal, often intergrown with quartz, as in this piece. It bears the number '848', added by the Edinburgh mineralogist Robert Jameson in 1809, when he reorganised and catalogued Hunter’s minerals, by then in the Hunterian Museum, for which task he was paid the astonishingly large sum of £100.

William Hunter and assistants

William Hunter and assistants

The arteries of the intestine

1746–83

Portion of human gut with mesentery, turpentine and glass jar; Portion of human gut and glass jar; Portion of human gut with mesentery, turpentine and glass jar

These beautifully made preparations, two wet and one dry, show diverse methods of illustrating the same anatomical feature and may represent technical experimentation. In each, a length of intestine has been prepared to show the branching of the fine arteries in the intestine wall. The specimen at left is injected black, inflated, the cavity of the gut distended with plaster of Paris, then coiled, dried, and mounted in turpentine. The specimen at centre is injected black, inflated, straightened out, dried, and varnished. The specimen at right has undergone the same process, however, in this case the cavity of the gut is open but empty; it is not known how this remarkable feature is achieved.

Jean-Siméon Chardin

Jean-Siméon Chardin

A Lady Taking Tea

1735

Oil on canvas

This painting is considered one of Chardin’s greatest achievements. By 1765, the year in which it was spotted by William Hunter in a Covent Garden auction room, at least twenty-five pictures associated with Chardin had gone through the London sale-rooms. As the owner of three such pictures by the end of his life, Hunter was among the artist’s most important British collectors. Hunter’s friendship with Scottish painter Allan Ramsay would have helped him to appreciate the French artist’s technique, such as the blurring of certain areas of the canvas to focus attention on the head of the woman and her hands at the tea-cup. And the presence in Hunter’s collections of several editions of key texts on the positive and negative qualities of new drinks such as tea, chocolate, and coffee, as well as a live tea-shrub (Hunter was instrumental in finding Queen Charlotte a specimen for her own collection of botanical curiosities) indicate he would have enjoyed the reference to tea-drinking.