Shell meets Bone

13 April - 13 August 2017

Hunterian Museum

Admission free

Introduction

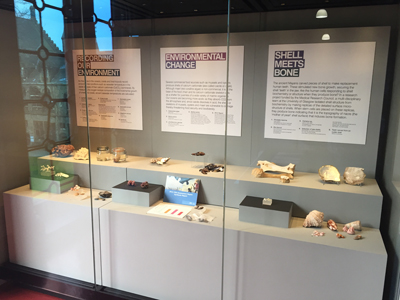

Shell meets Bone is a unique exhibition which combines biominerals from The Hunterian collection, cutting-edge University of Glasgow research and new artwork to explore the surprising links between shells and bones.

Shell meets Bone is a unique exhibition which combines biominerals from The Hunterian collection, cutting-edge University of Glasgow research and new artwork to explore the surprising links between shells and bones.

Shown across two spaces in the Hunterian Museum, the exhibition reveals the result of collaboration between biominerals expert Professor Maggie Cusack and artist in residence Rachel Duckhouse.

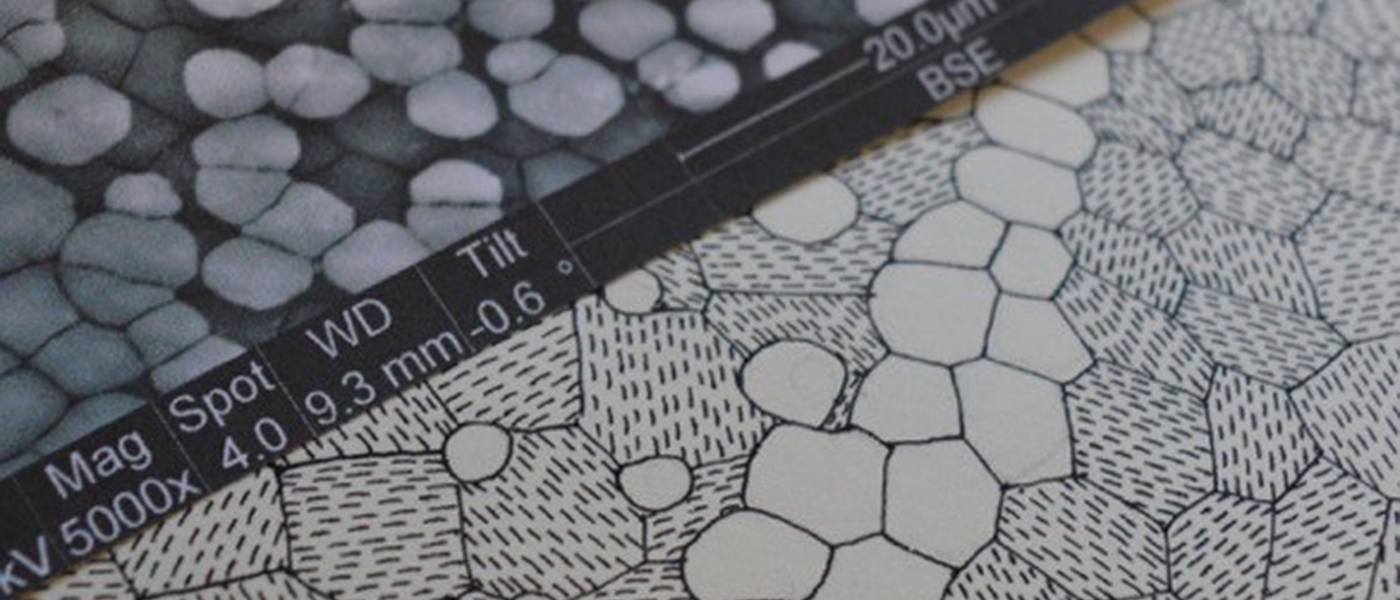

Biominerals are minerals made by living organisms, including us, and used to produce hard structures such as teeth, bones, shells and coral. Professor Maggie Cusack’s research focuses on the intricate nano-patterns within sea shells and what they tell us about the wider world.

Research has shown that, on a nano scale, the patterned surface of mother of pearl shell (nacre) can stimulate human stem cells to make bone. Exactly how and why remains a mystery.

It is this mystery that prompted Professor Cusack and Rachel Duckhouse to work together, to see if their parallel fascination in the patterns of nature could inspire new questions and ideas.

Shell meets Bone

Organisms produce (bio)-mineral structures for skeletal support, dentition and protection.

Organisms produce (bio)-mineral structures for skeletal support, dentition and protection.

Research at the University of Glasgow includes extracting information on past climates from such structures, determining how marine biominerals will be affected by environmental change such as ocean acidification, and exploiting the fine structure of tropical marine oyster shells to reveal fundamental principles of how shell and bone grow in living organisms.

It may not seem that a mollusc and a human have much in common in the first instance but cutting-edge multidisciplinary research, bringing together Biology, Engineering and Earth Science has revealed unexpected results that may have profound implications for human health.

This Medical Research Council-funded project attracted the attention of artist, Rachel Duckhouse, who was already fascinated by patterns in nature.

This Medical Research Council-funded project attracted the attention of artist, Rachel Duckhouse, who was already fascinated by patterns in nature.

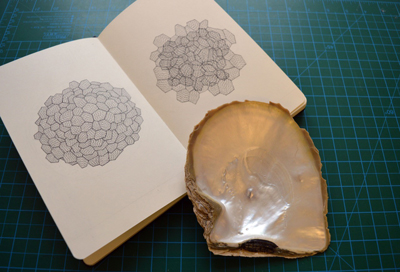

In a Leverhulme Trust supported art residency, Rachel worked with biominerals expert Professor Maggie Cusack to explore the beautiful nano-patterns of mother of pearl shell and their connection to the University of Glasgow’s research into human bone growth.

The resulting exhibition, Shell meets Bone, shows both new artwork created by Rachel Duckhouse throughout the project and explores Professor Cusack’s fascinating research.

A Conversation about Shell meets Bone

A conversation between Professor Hayden Lorimer, Professor Maggie Cusack and Rachel Duckhouse about Shell meets Bone.

HL: So, all collaborations need some kind of origin story… and yours begins with a fascinating cultural artefact from ancient human history. Can you tell me more about it?

MC: I’d come across an account of Mayan people using shells as teeth. The carved pieces of shell were actually integrated into the jawbone - new bone had formed around them. It’s completely counter intuitive, the fact that shell – calcium carbonate – could become part of a calcium phosphate human skeleton. We expect foreign objects to be rejected, whereas these were accepted, and I was fascinated by that.

RD: You told me that story the first time we met, and it really sparked my interest in your work. I thought of how we graft different kinds of trees together – that physical intertwining of species - it made me think about the material properties of our skeletons and how they can combine with non-human materials, on a biological level.

MC: It’s intriguing on so many different levels, and the obvious question for me was: what is it about nacre, or mother of pearl, that those human cells were responding to?

Colleagues in the University had been working on how human cells respond to surface pattern. They produced a series of patterns of nano pits (or holes), from a perfectly uniform grid formation, to a slightly ‘offset’ version, to a completely random formation. The cells responded best to the patterns that were not perfect and not random. It was that sweet spot between chaos and order that they responded to by making bone. It got us thinking about back to that initial question – what is it about the nacre surface pattern that the cells are responding to? This really got Rachel and I talking.

HL: So you’ve described a remarkable entanglement of nature and culture. Ordinarily, when we humans look to nature, we seek harmony, pattern, grace in structure; but as you’ve described, that’s not really what you’re interested in here, right? There are aspects of form that fascinate you, where controlled disorder is what’s at work. Can you tell me more about what seems to me like a contradiction?

RD. It doesn’t seem to me like a contradiction because I find controlled disorder very harmonious. A pattern that is too regimented is quite boring in terms of how we process it visually. It’s when you get little glitches and moments where the pattern breaks, but the rules that control it are still there, that interest and beauty come into play.

In a human made artefact, or piece of music, there’s something interesting in the pattern when it shifts or breaks at certain points. Many things made by human hands have an unconscious element of imperfection within their making, and I’m interested in the connection between that and imperfection in nature. Like the branching patterns in a tree, created by a set of rules that makes them grow in a particular way, yet every single division and length within that branching system is slightly different. It’s a system full of rules which are very slightly shifting and unpredictable. There’s a degree of randomness but it’s still harmonious as a design, and beautiful somehow to us, more than a precisely engineered thing, that can feel lifeless. It’s that imperfection that fascinates me when I look down the microscope at Maggie’s work.

MC: I agree with Rachel – I think the contradiction is only an apparent one. We’re often looking for patterns and our eyes are drawn to them – and the ones we find the most aesthetically pleasing aren’t perfect. We’ve spoken a lot during the residency about that sweet spot. Before the residency, I would have convinced myself that there was more order to the shell than there actually is. Looking at it in that reflective way, you actually see where the imperfections are. We tend to create rules to say ‘it forms this way.’ and that accounts for a large proportion of what is happening, but in fact the rules are broken sometimes, just as they’re broken in your drawings.

HL: One of the great joys of spending time working with an ‘other’ person, is that you get to learn differently. Can you reflect a little about what you understand to have been a shared sensibility? It might be ‘playful curiosity‘ ?

MC: Playful curiosity is a great way to describe it. Rachel really interrogates the work and asks you questions you would just never have thought of, and that’s been really great to look at my work from a completely different perspective. She doesn’t start drawing until she understands things to a certain level. And then the understanding continues during the drawing process. There’s a communication which is very much two way and that has been really enriching.

RD: I didn’t know what Maggie’s process or approach would be, and it’s been wonderful to see how playful she is. She’s been working with these same shells for so many years, and she still has a smile on her face every time she looks at them. I’ve found that very inspiring to work with. It’s that joy of the mystery of them. What she doesn’t know is as fascinating to her as what she does know, and that excitement of not knowing is something I love to work with.

MC: We can think of the scientific approach as being rigorous – and much less playful than it should be. One thing that I’ve learned is that that combination of rigour with reflection - and that reflection can be fairly playful – is a really great space in which to work. If you’re only rigorous, you’re asking a particular set of questions, and those are the questions that you continue to ask, but if you can be more playful within those questions, there’s so much more potential for different kinds of answers.

HL: For many people, and I include myself in that; drawing is an inability rather than an ability. But drawing, when done in certain ways, is a means to make something visible. To show what would otherwise remain unseen, and thus less knowable. For those of us for whom the pencil point remains a blunted thing, can you as someone who draws as a core part of your creative practice, explain what is it that’s happening when you draw?

RD: I think maybe I’m trying to understand things. When Maggie explains something to me, I get an idea on the periphery of my mind’s eye. I’m trying to find out what it is that’s interesting to me about it. Is it the relationship between one thing and another – and what does that look like? What’s the balance of it, the tension in it? It comes down to putting two lines on a piece of paper and trying to figure out what their relationship is and what’s beautiful about it.

HL: So at its core it’s almost non representational?

RD: Yes, and when I get down to the nub of it, my drawings help me distil what it is about the world that I find beautiful. And it might just be two lines sitting together. Talking to Maggie about how these shells are put together, what their architectural structure is, what relationship does one element within that architecture have with its neighbour... there’s something about that mystery that I want to describe and understand in a visual sense.

HL: Invisible to the recording of this conversation is the animated use of hands... and I know that this non-verbal communication, particularly when we’re seeking to come up with accessible scientific explanations, is something that you’ve found quite appealing. Can you tell us about when you saw this at work and why you saw it as consequential?

RD It’s been so funny and lovely to see completely different people using their hands to describe the movement of cells… whether it was a biologist, zoologist, geologist, bio engineer, or a biominerals expert, everyone used the same movements of the fingers and hand, and I’d never seen that before, it was like a universal sign language.

HL: A kind of artistry?

RD: Yes. A cell doesn’t have a set shape of its own, it’s the response to its environment that gives it shape. So the hands represent communication between different people using a gesture or signal.. and the fact that cells move and differentiate using signals within themselves. These signals are derived from the cell’s relationship to the surface pattern it’s on. It’s all about signals and relationships.

HL: The exhibition represents the end point of the residency, but I have a sense that it’s not the end of your interests. What do you think are the legacies of what you’ve learnt? Where do you take things next?

RD: This exhibition represents a starting point really; a snapshot of what I’m thinking about. It will take years to process everything and develop the ideas.

There are so many tangents to go off on. Maggie’s introduced me to lots of her colleagues and in particular there’s a bio engineer called Nikolaj who works on the nano pits stuff - he’s responded really interestingly to our work - he’s designed some software as part of his research, as a direct result of looking at some of the dot drawings I made, and that’s something I’m hoping to follow up on.

MC: What’s so fabulous about the Leverhulme Trust scheme is that’s it’s so open ended. It allows you space to reflect, not have a specific target or deliverable. For me, the idea of combining that rigour with the reflection and the playfulness is something that I’m sure will stay with me, and the stepping back from what I’m looking at. Rachel and I will continue to work together.

RD : Yes! There are so many more questions, I could work on this for years.

MC: There are always more questions than answers.

Professor Hayden Lorimer is a cultural geographer, who writes geographically about landscape, memory, biography, and the life of the senses. He is a happy collaborator, with artists and scientists, and teaches in Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow.

Professor Maggie Cusack’s research examines a range of biominerals including molluscs, corals and brachiopods.

Rachel Duckhouse is a visual artist based in Glasgow. She has undertaken several research based artist residencies in the UK and abroad and has exhibited work in the UK and internationally.

Acknowledgements

Shell meets Bone has been supported by:

Shell meets Bone has been supported by:

The Leverhulme Trust

Medical Research Council

University of Glasgow School of Geographical and Earth Sciences

We would like to thank Mr Les Hill, Mr Peter Chung, Dr Nick Kamenos and Professor Hayden Lorimer of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow for their help and support.