Symposium: Addressing Inequalities within Sustainable Development

Published: 8 March 2021

This symposium seeks to critique the United Nations 2030 Agenda for sustainable development goals in relation to addressing inequalities.

A summary of the March 8th Symposium: Addressing Inequalities within Sustainable Development.

In 2001, the United Nations set forth the Millennium Development Goals that provided a unified agenda towards alleviating inequalities across the world. This agenda was in response to growing criticism that the benefits of globalization were unequally distributed, while its costs were borne by all (Jane, 2016). The MDGs largely focused on poverty reduction through a donor centric view of development, and lacked a clear focus on aspects such as human rights, empowerment, and equity. In 2015, the MDGs were superseded by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that took a more people-centered comprehensive, inclusive and integrated approach to development. The United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development provides a blueprint for global peace and prosperity for all people with a focus on the interplay between the 5Ps of people, prosperity, planet, partnership and peace (UN, 2015a). Its 17 Sustainable Development Goals recognize that ending global poverty and other deprivations requires all countries, developed and developing, to work in a global partnership to improve health and education, spur economic growth, address climate change and preserve the natural environment.

Many people globally still live under conditions that do not meet their fundamental needs. Therefore, as nations across the globe integrate SDGs into their national development and sustainability plans, it is critical that we address inequalities in the agenda in relation, but not limited to, race, gender, class, ethnicity and nationality. Some of the main concerns surrounding SDGs are that they are not binding on countries, and do not hold those in power accountable for their actions. Furthermore, the goals ignore the underlying systemic inequalities in the international system and rely on a top-down bureaucratic approach that ignores local contexts.

Given these critiques, on 8th March 2021, lead members of the ‘Addressing Inequalities’ interdisciplinary research theme from the University of Glasgow’s College of Social Sciences hosted a symposium as part of the Addressing Inequalities Month which sought to promote critical knowledge exchange on the sustainable development goals and the inequalities embedded within them. Given that March 8 was International Women’s Day, the symposium also offered an opportunity to reflect on gender-specific concerns in relation to SDGs.

The symposium included four keynote speakers: Nicole Busby, Professor in Human Rights, Equality and Justice in the School of Law; S. Vittal Katikireddi, Professor of Public Health & Health Inequalities at the MRC/CSO Social & Public Health Sciences Unit, Institute of Health and Wellbeing; Daniel Haydon, Professor of Population Ecology and Epidemiology at the Institute of Biodiversity, Animal Health & Comparative Medicine in the College of Medical, Veterinary & Life Sciences of the University of Glasgow; and Michele Schweisfurth, Professor of Comparative and International Education at the School of Education at the University of Glasgow.

The presentations and discussions raised many key issues in relation to addressing inequalities around SDGs.

Women’s Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Feminist Critique - Prof. Nicole Busby

Professor Busby initiated the conversation by providing a feminist critique to women’s rights and the sustainable development goals. She raised three important issues. Firstly, while significant improvements have been made to mainstream gender equality and women's rights issues under SDG 5, she described how the SDGs fail to identify gendered injustices embedded within the economic and social structures that produce barriers to women’s and girls’ equality. She further added that the SDGs risk reproducing existing inequalities and re-entrenching barriers to the full realization of women's rights, a risk that has been heightened by the disproportionate gendered impacts of the current COVID pandemic. Secondly, the SDGs do not tackle the question of what development is and how it can be best achieved, and instead assume that economic growth and gender equality are directly linked, thereby containing no strategy for structural reform. Thirdly, pointing to the UK context, she highlighted how the pandemic brought to the fore the inadequacies of the current employment rights framework, the insecure nature of certain types of work (and the low value placed on these), which are closely linked to the gender, race, and class of those who performed such work. She underscored the need for a strong human rights language in the SDGs that is currently missing and asserted that the agenda does not aim high enough in respecting, protecting, and fulfilling human rights.

To overcome this blind spot and to respond to existing gender injustice, Prof Busby recommended the need for SDGs to focus on inclusive development rooted in social justice, rather than solely on achieving narrow economic growth. She also spoke about how we must resist the assumption that women and girls are exceptionally vulnerable. Vulnerability is a human condition, but what varies is our ability to build resilience. She argued that this ability is based on structural and institutional inequalities of power, which influence access to necessary social, economic and political resources. Moreover, there is a need to recognize that women’s experiences need to be integrated within social and economic institutions in order to disrupt these institutions and the relationships of power that serve them.

SDGs, ethnicity, and health inequalities- Prof. Vittal Katikireddi

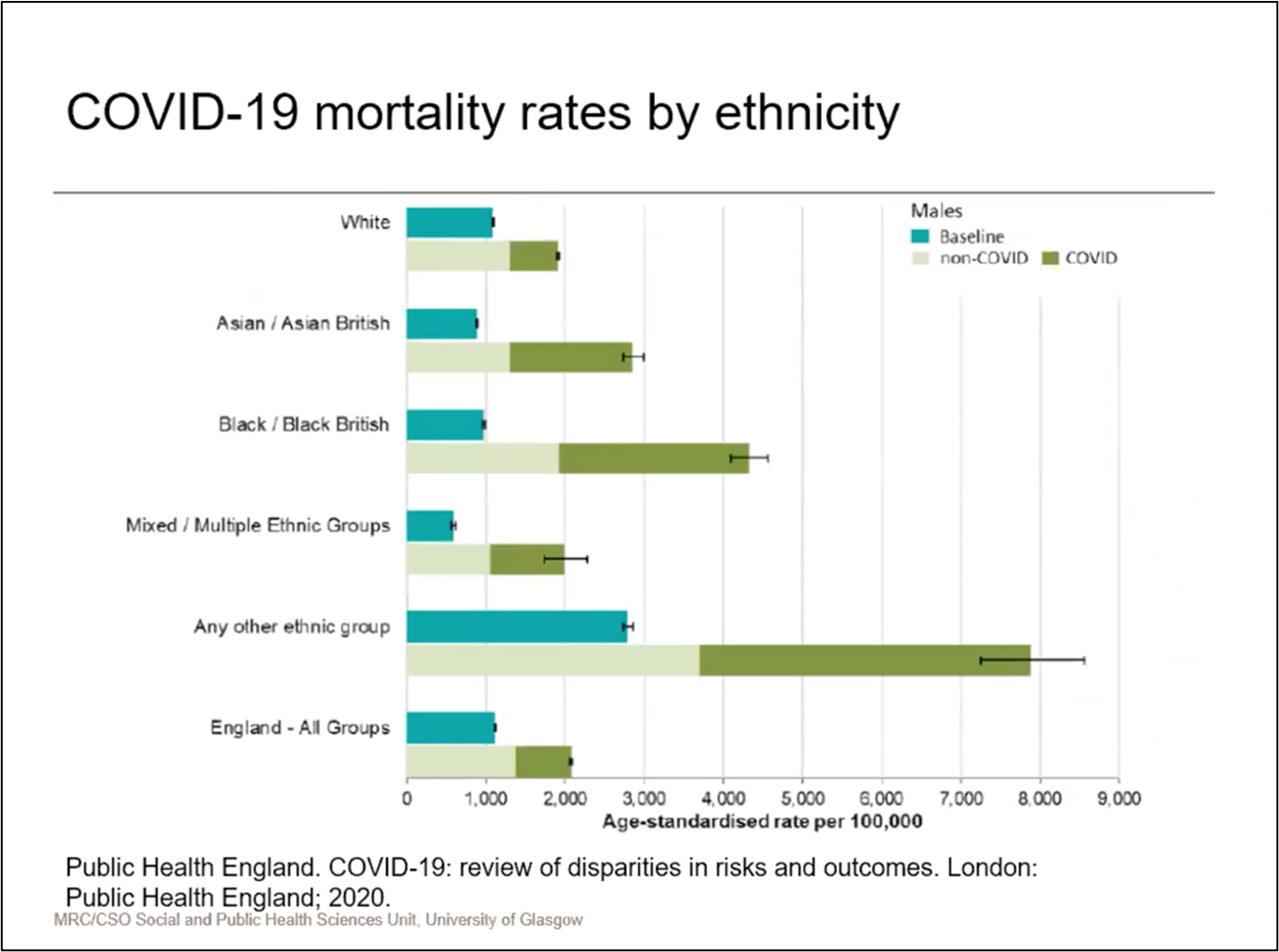

The second speaker, Prof. Vittal Katikireddi, introduced the need to locate health inequalities within the larger context of racial and ethnic inequalities in societal institutions. He argued that the SDGs paid little attention to ethnic and race inequalities in relation to health, and suggested that a person’s physical features, the language they speak, diet, religious beliefs etc. may have an impact on how they are treated within society, which, in turn, can have major implications from a health point of view. He demonstrated how large differences in COVID-related risks in the UK are driven by social processes, and not biological differences, across ethnic groups. These processes and mechanisms include differential access to social resources, differences in types of occupations, etc. The diagram below shows how despite pre-pandemic mortality rates of certain ethnic groups being better than whites, the mortality rates across all minority ethnic groups was amongst the highest during the pandemic.

Thus, when thinking about SDGs, many social determinants of health are crucial in influencing ethnic inequalities. The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn attention to the importance of addressing racial and ethnic inequalities in the UK and internationally. Prof. Katikireddi stressed on how such inequalities are likely to continue given the threats posed by the climate emergency and the large migration flows that will result. Thus, he argued that the sustainable development goals need to include ethnicity, race and migration within them in order to ensure that these goals are met.

How One Health approaches can help address inequalities -Prof. Danial Haydon

Glasgow is an international leader in One Health research. The term ‘One Health’ describes the collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment. According to Prof. Haydon, One Health is particularly important given the current context of the pandemic, as its pathways can help curb various diseases in animal populations before they transfer to humans. He suggested that these included reducing contact between (non-domesticated) animals and humans, actively managing animal populations through vaccines and medications, and culling animal populations when infected.

- Haydon emphasised how One Health has wider implications for poverty and gender equality, conservation and food security, and economic well-being. For example, post-exposure medication can be hard to obtain and quite expensive, and many people, particularly in the Global South, are unable access it. Therefore, one way to manage the spread of disease is by vaccinating animals and controlling infection before it manifests in human populations. He argued that vaccinating animal populations also brings wider benefits beyond health, and that these included improved animal welfare, productivity and economic value, which, in turn, can lead to greater food security and more widespread societal benefits. To support this argument, Prof Haydon shared a study that evidenced how a livestock vaccination programme in East Africa translated into better school attendance by girls, because it created more stable and increased household incomes. He ended by advocating that the best way to prepare for the unexpected is to strengthen basic health care around routine infectious diseases, and emphasized the importance of universal and sustainable access to vaccines to ensure equality of health globally.

- Schweisfurth ended by arguing that quality teaching and learning matters most for the disadvantaged, as the school environment is where they lean heavily for most of their education. She further suggested that COVID has deepened educational inequalities and that schools are going to have a huge role in trying to redress some of the imbalances that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Quality Education: Discourses, indicators, and the implications for equality- Prof. Michelle Schweisfurth

Prof Schweisfurth started by pointing out that despite the Millennium Development Goals focusing on achieving universal primary education for all children, statistics showed that enrollment rates had not gone up during that period. In fact, the most disadvantaged (such as girls with disabilities, indigenous people, lower income families and rural children amongst others) were the worst affected by the learning crisis. As a result, the Sustainable Development Goals are no longer just about access. Instead, they promote inclusive, equitable, quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all. However, despite this positive change in focus, Prof. Schweisfurth argued that despite the discourse on equity and quality, current monitoring frameworks continue to use quantitative metrics with little emphasis on what really happens in schools and classrooms to support quality learning. She underscored the need to review the way we assess outcomes in order to gain the evidence about the processes that underpin quality schooling that is essential to develop. However, she cautioned that what might work in one cultural context, may not be appropriate for another cultural context. For example, her own research has shown that despite learner-centered pedagogy being embedded in post 1990s education policies across sub–Saharan African countries, it has had very little impact at the classroom level.

Conclusion

While the SDGs are a significant improvement over the MDGs, they do suffer from certain shortcomings that mostly arise due to their failure to address embedded structural issues that underlie current economic and political systems. The symposium highlighted some of these issues from diverse perspectives including health, education, feminist critiques and overall development. Together these critiques are important to take into consideration to make SDGs more effective globally.

References

Briant Carant, Jane (2016). Unheard voices: a critical discourse analysis of the Millennium Development Goals’ evolution into the Sustainable Development Goals. Third World Quarterly, (), 1–26. doi:10.1080/01436597.2016.1166944

Fukuda-Parr, S. (2016). From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: shifts in purpose, concept, and politics of global goal setting for development. Gender & Development, 24(1), pp.43–52.

First published: 8 March 2021