Hutchesontown

Source: Aerial Photograph from Glasgow Corporation records (Mitchell Library), early 1960s, as featured on Lost Glasgow facebook page

To find out more about what it was like to live in a high rise flat in Hutchesontown follow the following links to read responses to our online questionnaire or listen to extracts from oral histories conducted for the project:

Online Questionnaire Responses

Online Oral History Resource

Brief History of Hutchesontown in the post-war years

Hutchesontown/Part Gorbals Comprehensive Development Area was given formal approval by the Secretary of State for Scotland in 1957. This was Glasgow Corporation’s way of disposing of the notorious slum areas of the Gorbals, of ‘No Mean City’ fame, while creating a new ‘modern’ showpiece innercity housing estate, or five to be exact. Hutchesontown as part of the Gorbals had a long history of being associated with crime, vice, poverty, poor health and overcrowding. It’s not surprising that the Corporation started its programme of clearance and rebuilding in this location.

Prestigious and well-known architects were awarded contracts to build high rise estates with a ‘modern’ aesthetic, reflecting contemporary architectural fashion and practice. Hutchesontown ‘A’ was low rise housing, mainly maisonettes completed in the late 1950s; Hutchesontown ‘B’ was designed by Robert Mathew and contained four 18 storey blocks; Hutchesontown ‘C’, the most famous of all the areas, was designed by Basil Spence; Hutchesontown ‘D’ was designed by the SSHA’s chief technical officer Harold Buteux and was the largest area and included four 24 storey blocks and three 8 storey blocks; finally, Hutchesontown ‘E’ comprised of twelve 7-storey deck access blocks and two 24 storey point blocks.

This layout followed the recommendations of the Bruce Report of 1946 for modernising and replanning the city within its existing boundaries. The Bruce plan hoped to retain the city’s population through high density building. The opposing Abercrombie plan which was regional in outlook argued for a more even distribution of population throughout the Clyde Valley, which meant moving 250,000 to 300,000 people out of Glasgow to ease congestion.

The Government, with the support of the Scottish Office, favoured the Abercrombie plan which resulted in the establishment of an ‘overspill programme’ and the building of new towns, of which East Kilbride was the first. However Glasgow Corporation went ahead with its plan to retain its population through high density building and the Government approved Hutchesontown/Part Gorbals as a pilot CDA programme in 1954. The Corporation wanted to adopt a similar approach in Royston and Govan. Glasgow Corporation was to designate 29 CDAs, of varying sizes, throughout the city, the most comprehensive use of this redevelopment strategy in the UK (although not all of these plans were fully realised).

There seems to have been much excitement within Scotland’s architectural community concerning the planned Hutchesontown/Part Gorbals CDA. Ninian Johnstone, a prominent Glasgow based architect, wrote an article entitled ‘Miracle in the Gorbals?’ (after the ballet of 1944 of the same name?) in Architectural Prospect, which described the CDA as ‘the largest of its kind so far attempted’ and ‘one which bids fair to make history’.

Hutchesontown/Part Gorbals comprised at the planning stage 111 acres of ground on the south bank of the Clyde between Crown Street to the west, Waddel Street to the east and Caledonia Road to the south. Much of the four storey tenements that would be cleared only dated from around 1850 to 1890 and Johnston described it as an area which had ‘deteriorated rapidly’.

These photographs, taken during the construction of Spence's Queen Elizabeth Square show the tenements which were being replaced:

Source: Queen Elizabeth Square under construction, early 1960s, skyscraper city (image widely available online)

Source: some more last days of the Gorbals, early 1960s, urban Glasgow (image widely available online)

In 1957 the area was predominantly residential and the following statistics provided in Johnston’s article give a sense of the overcrowding and lack of internal amenities in the flats:

Total number of dwellings 7,605

One and Two Apartment Houses 87%

Back to Back Houses 33%

Houses with Baths 3%

Houses with Internal WCs 22%

Houses unacceptable Sanitarily 97.3%

Average number of persons per room 1.89

Average number of persons per acre 458.6

Industry was described as being ‘unimportant’ in the area with only 11.7 acres occupied by small concerns. Notably there were 394 occupied shops (50 unoccupied), 48 public houses and other community facilities.

Johnston also stated that ‘beneath the statistics’ there were ‘strong characteristics, a local spirit’ which ‘must be carefully preserved while the buildings are being demolished’. As he suggested:

“People who have moved out of this area to new housing districts at Drumchapel, Pollock and elsewhere are known to make the journey back to their old haunts of an evening to meet their friends in the pubs, the chip shops and the cafes. Some have even forsaken the modern convenience of their new surroundings and returned to their old ones. This is an attitude to be respected, as it represents a strong feeling for locality, which is essential in the structure of a healthy community.”

The area was to be completely demolished and rebuilt as follows:

Residential 62.1 acres

Schools 19.0

Industrial Service Trades 2.9

Commercial 3.4

Community Facilities 6.3

Open Space 5.5

Roads and Car Parks 12.0

It was expected that development of the area would take twenty years and in the first stage a main shopping centre, clinic, cinema and ‘services trades area’ would be built. Stages two and three would include the schools and the completion of local shopping centres and a community centre. There was to be 57 shops replacing the 444 existing in 1957. The 48 pubs were to be reduced to 9. Industry would not be relocated in the area but sites would be made available in areas zoned for industrial use for those firms displaced.

Source: some more last days of the Gorbals, 1960s, urban glasgow (image widely available online)

In terms of the proposed layout, the main objective was to eliminate through traffic and ‘create an integrated plan’. There were to be small parks to act as central open spaces, with playgrounds and nursery schools included for the same reasons. Johnston in true architectural fashion also stated that ‘the development will also have a very important effect on Glasgow’s skyline’. The plan to build several point blocks and slab blocks was welcomed as ‘at present’ Glasgow has ‘generally the rather dull effect of having been chopped off four storeys above ground level, so that the impression is gained of proceeding along a series of gigantic trenches’. The new development would also ‘give back to use the space which is stolen by Glasgow’s countless back courts’.

It was expected that the total cost of acquisition, demolition and development would be almost £13m (approx £284m today). Undoubtedly the final cost would have been higher. The Spence blocks at Queen Elizabeth Square, for example, suffered both from construction delays and went over budget.

Our case studies

Pearl Jephcott did not choose any of the areas of redevelopment in the Hutchesontown/Part Gorbals CDA to be one of her case studies in the 1960s. However given the area's iconic place in the city's history, as well as its central location in the city and the large proportion of high flats built in a concentrated area (high density building) we have decided to focus on the following multi-storey flats:

Queen Elizabeth Square

Source: P. Jephcott and H. Robinson, Homes in High Flats, (Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh), 1971, Plate 16

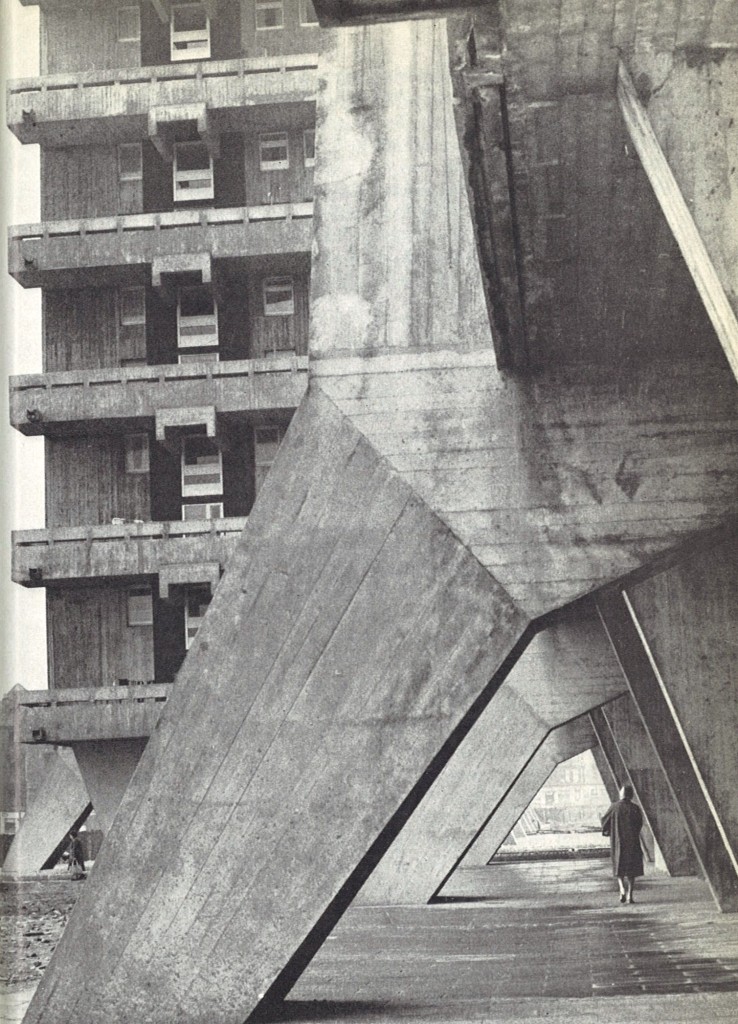

We have chosen to focus on Hutchesontown ‘C’, the blocks designed by Basil Spence, mainly because his buildings were nationally, if not internationally, renowned at the time they were built. The design was obviously influenced by Le Corbusier and thus Hutchesontown ‘C’ was a good example of ‘modernist’ architecture popular in the1960s. It was also hailed as a good example of ‘brutalist’ architecture, which has had a revival in recent years in terms of its popularity in architectural circles. See for example 'Scottish Brutalism' a University of Strathclyde Department of Architecture research project which aims to map, document and critically assess Brutalist architecture across the Strathclyde region. However ‘modernism’ soon became unpopular in the 1970s and suffered a back-lash, with ‘post-modern’ architecture becoming the new movement in the 1980s. The Spence blocks even had a ‘post-modern’ makeover in the 1980s when the architectural equivalent of pointy hats were constructed on top of the building.

The job architect, Charles Robertson, discussing the blocks at a conference in 1992 (see Miles Glendinning, Rebuilding Scotland: The Postwar Vision 1945-1975 (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 1997), pp. 92-102), stated that Spence’s brief was to build three slab blocks. He was required to build 400 individual dwellings, of five different types. Lifts were to stop on alternate floors in order to be more ‘economic’ – hence the reason why the houses were maisonettes. Robertson describes the slabs as being ‘composed, in effect, of ten individual “towers’ each 40 feet square’. They were linked by communal balconies or ‘garden slabs’. These balconies were seen as ‘a perpetuation of the green’ and as ‘a space for some tubs of flowers, and to hang out the washing, to give the baby an airing, and to provide a garden fence to gossip over’. Like Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation (see our blog 'Glasgow goes to Marseilles') Spence’s blocks were also on stilts, which was supposed to allow the space under the building to be used by the community. However what the Spence blocks lacked were the inbuilt recreation, shopping and educational facilities which Le Corbusier’s block had.

Robertson, reflecting on the state of the building suggested that the concrete ‘had not weathered at all well’ and had ‘deteriorated in many places’ with the reinforcing being ‘exposed in several places’. He admits that the building had ‘not been popular’ and crucially had not been maintained for twenty years. As he states:

‘What we did not realise when we were building things of this nature is that they involve a very high maintenance cost. And that cost was impossible for the local authority to deal with’ (p. 101).

Hutchesontown ‘C’ was demolished in 1993. People were, and continue to be, vociferously divided over the merits and failures of the blocks, regardless of whether they themselves lived in them or not. See for example 'The Gorbals Block debate' on 'The Joy of Concrete' website. Or the opinions of residents and architectural experts etc in a BBC documentary 'High Rise and Fall' from 1993.

Waddel and Commercial Courts (Riverside Estate)

Source: Waddel Court under construction, August 1962, image C3325, ©Virtual Mitchell

The blocks by Robert Mathew, now known as the Riverside Estate are also interesting in that all four of the blocks and the low rise flats that accompanied them are the only part of the Hutchesontown/Part Gorbals CDA which has survived fairly intact. Having received a £6million refurbishment which was completed in 2008, these high flats are considered to be fairly popular.

Source: Hutchesontown B, 1958, Historic Scotland, Scotland: Building for the Future, Essays on the architecture of the post-war era

Mathew was a leading figure in the architectural profession when his firm was awarded the contract, he had designed the redevelopment of the University of Edinburgh's George Square and the Tower Building at the University of Dundee. He insisted that the blocks at Hutchesontown 'B' be build at 45 degree angles to the road plan as this was best for maximising daylight. Like Queen Elizabeth Square, the flats were built over two levels, maisonettes, with the lifts stopping on alternate floors. All flats had balconies. Mathew also pioneered the lighting of the roof space, which he described as 'public theatre', that many blocks in Glasgow now have.

Waddel and Commercial Courts do not seem to have divided opinion in the same way as Queen Elizabeth Square. The design and construction was more straightforward, perhaps there has been less problems with water ingress and damp.

Source: Riverside estate today

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Some material on this website is not being made available under the terms of this licence.

These are:

Third-Party materials that is being used under fair use or with permission (photography owned by archives, blog contributors or from WikiMedia Commons). The respective copyright/Creative Commons licence details for use of third-party material should be consulted.