The English have a miraculous power of turning wine into water (…energy, and food)

Published: 8 August 2017

Reflection on a WEFWEBS workshop concerning the future of the UK Wine Industry

I’m not exactly sure what Oscar Wilde meant when he said it, but I imagine turning wine into water might refer to turning something wonderful into something less so. In what follows however, we explore briefly the results of a workshop in which wine is unravelled as a mix of water, energy, food, the environment, culture and technology – something as interesting and complex as UK Wine itself.

At the end of June (2017), the WEFWEBS research team assembled at the Ridgeview Wine Estate, Ditchling, together with a number of representatives from the UK Wine Industry to explore the future of UK Wine and the role Smart-Technology might play in that future.

As with all WEFWEBS stakeholder engagement efforts, the idea here was to draw together and map out the interdependencies between water, energy and food, but with an added interest in the different ways wine and technology also participate in these interdependencies.

With this in mind, the aim of the endeavour was to consider the desired vision for the UK Wine Industry, and to imagine what a resilient industry might comprise, under various and uncertain, future environmental, socio-economic and socio-political scenarios.

Although brought together under the auspices of a workshop, as has been the case for other WEFWEBS arrangements, the participants and researchers here were able to break out of the workshop space, into a vineyard, into a wine production facility, and even drink a little wine together. As a result, the arrangement was able to situate the researchers and participants in the practices of growing grapes, making wine and appreciating it, and therein raise a new awareness of the many different elements that comprise UK Wine.

In the vineyard, we learn about the types of grapes used at this particular winery. Pinot Noir, Pinot Meunier, and Chardonnay – Ridgeview produces sparkling white wine. The practices are collectively termed cold climate viticulture, and have been borrowed and adapted from similar climactic, topographical and geological regions in France (think Champagne). We further learn how vineyard managers in the Sussex wine-producing region use weather data to predict frost conditions. They also meet together and exchange experiences in an effort to manage frost effectively – that is – the extent to which they need to get up in the middle of the night to check for frost and appropriately ignite hundreds of canisters of wax peppered throughout the vineyard in order to raise the air temperature between the vines. Growers and producers also meet together to agree upon prices for grapes produced so that the effects of frost don’t make grapes too cheap or too expensive – their livelihoods and the wine depend on it.

Caring for vines and berries is also a delicate balancing act; it requires a lot of skill and attention. Leaves are trimmed from the vines such that there is enough airflow and sunlight around the berries to ensure that moisture doesn’t accumulate and promote mould and mildew. Enough leaves must remain however, in order to shade the berries from sunburn, and to synthesise energy from the sun into food for the plant.

The trimming leaves also illustrates a number of different aspects of wine production. The weight of the trimmed leaves can communicate to the manager an estimate of the yield for that season, which in turn is communicated to the CEO and informs her business strategies going forward. The manager indicates to us that the more you know about the vines, the better the wine produced will be. The trimming of leaves, as well as harvesting and pruning, also employees the majority of seasonal workers who come from all across Europe year after year. Speaking with some of the Portuguese workers, the Ridgeview community has become like a family for them.

In the wine production facility, we stand amongst grapes being pressed and processed. Grape skins are filtered out and sent to farms for animal feed, or to distilleries for spirit production. The grape juice is then stored in massive stainless steel tanks, in which tartaric acid is removed, and malic acid is converted to lactic acid in malolactic fermentation processes. There is water too, used in the washing of grapes, bottles, tanks and the production floor, but it is also captured, treated and recycled. There are pumps, hoses, sensors, gauges, monitors, power connections and employees all working together to ensure that all is running smoothly.

Beneath us is the cellar where wine filled bottles are left to ferment for a number of years in a controlled climate. Each bottle is periodically rotated by hand to encourage spent yeast into the bottle’s neck for its later removal via chemical freezing. We watch as robotic arms and actuators swiftly move and cork the bottles ensuring the wine and its gases don’t escape once the yeast is removed. There are workers here too, moving bottles and crates, loading trucks and documenting deliveries for markets elsewhere.

Clearly, there is a lot of work that goes into making wine. However, much happens when drinking it too. Over glasses of UK wine, the researchers and participants learn more about the complex flavours of what they are drinking, from tropical fruits, melons and apples to the buttery texture and notes of brioche, as well as establishing an eye for the number and size of the bubbles effervescing in the glass and experiencing a new spectrum of colours. The participants and researchers also talk amongst themselves. One such conversation describes a long family history that dates back to William the Conqueror and the arrival of the Normans in England. Another, a more recent story of moving from Normandy to the UK to assist with horticultural science studies. Here, there is a shared historical and geographical space for some of the participants despite being from England and France respectively, but there is also a space where a tradition for working the land and the new but quickly developing educational programs and institutes dedicated to viticulture and wine making in the UK connect.

In the workshop space, it is the future that comes into focus. The group is presented with a myriad of possibilities for what technology can offer with respect to the ways we farm, how we manage resources, the types of data that can be generated, and what can be communicated around the globe. There is the possibility for vineyard managers to more closely monitor leaves and berries with heat profiling and soil moisture content, and technology that allows the precision application of irrigation and pest and disease management. There are also drones that can zap weeds out of existence, autonomous machines that can manage harvesting, pruning and picking, and robotic bees that can replace their fuzzy counterparts as far as pollination is concerned. The local environment is sensed and monitored too, giving wine makers a clear image of how water use, pesticides and fertilizers shape the ecosystems that surround their production.

Through technology, there is an opportunity for improving yields and quality, and for optimizing the use of resources. But there are concerns too. Concerns for what types of data might become available to who, what this might mean for competition in global markets, or the price of pesticides if chemical companies know when you need it most. There is also a concern for what might happen to jobs and families where automation is concerned, or whether we might want to concentrate our energy on saving bee populations rather than replacing them.

Through these activities, the researchers and participants together begin to form a picture of the different ways technology, the environment, people, histories, cultures, markets and so on play out, come together and even interfere with each other in complex, materially and discursively heterogeneous ways. For such a stakeholder engagement workshop, this is perhaps an outcome in itself, but for the group, this complexity and concern is also generative.

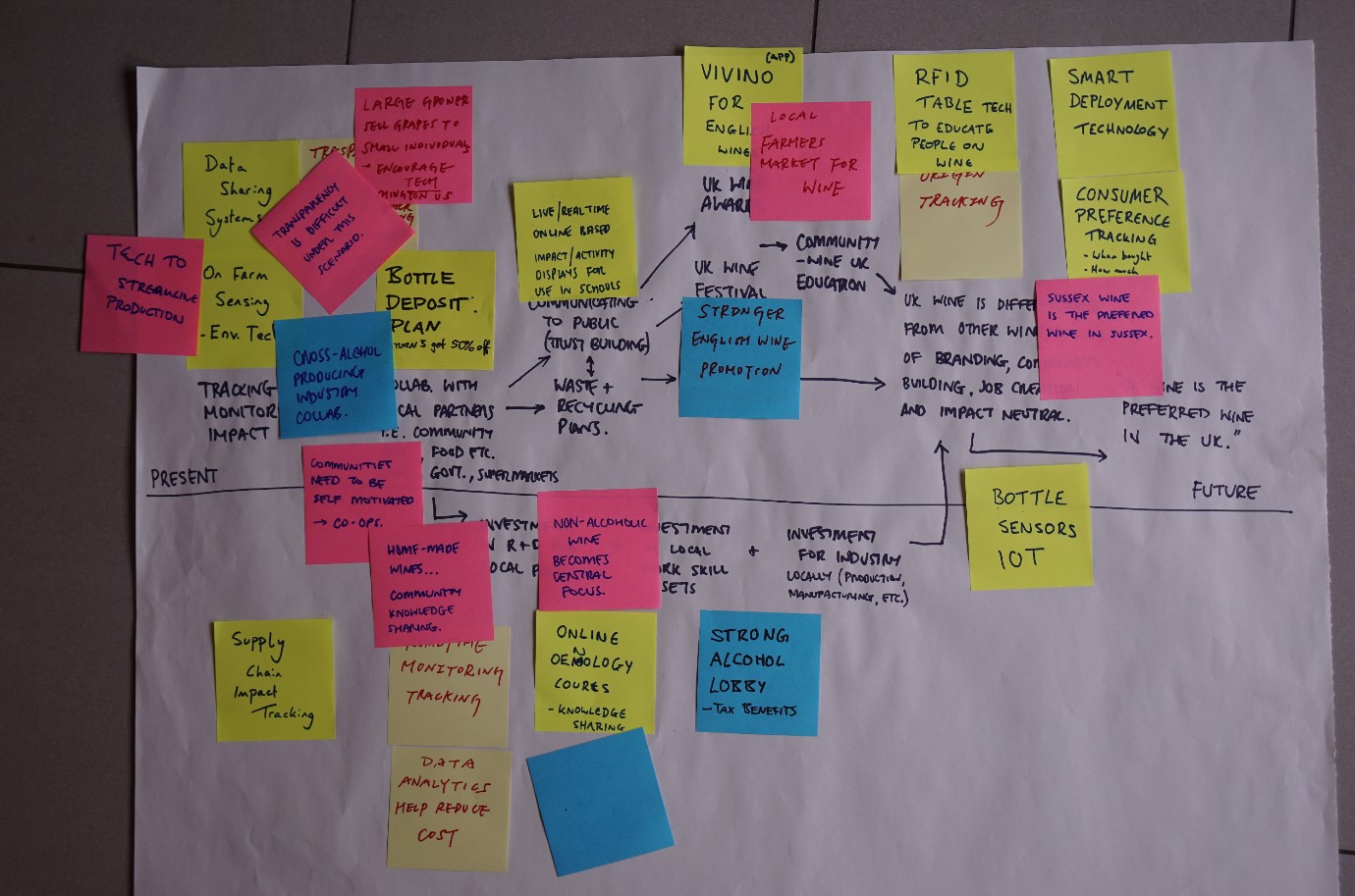

The researchers and participants set to task in translating these differently connecting and interfering aspects of present and future wine making into visions and plans for the future of the UK Wine Industry in informed and creative ways. The working groups agree to focus on how the UK Wine Industry might become a model for sustainable agricultural practices, producing consistently high and high quality yields, and producing wine that is the preferred wine in the UK.

The outcomes of the exercise are a series of maps that illustrate pathways to a desired and resilient UK Wine Industry with a surprising sense of scope and scale. The maps comprise considerations for berry weights and millimetres of water, to engagement with government and environmental groups on a national scale, to imported water and energy in the form of foreign produced bottles, sensors and equipment. They also comprise ideas about what role UK Wine might play in the promotion of a nutritional and varied diet, the creation of jobs, what new communities may be formed and what new stories may be told about UK Wine.

The maps are not exhaustive in their detail, there is of course only so much that can be produced in a day and a half. What has been clearly achieved however, is a new set of tools for understanding the precarious ways in which water, energy, food, wine, technology, people, the environment and so on are connected. For the researchers, the maps may provide a space in which we can ask questions about how these connections are made, how we might study them and how we might intervene in them. For the participants, the maps and the workshop have provided a point of departure to make connections and plans between themselves, and with the researchers, to investigate further pathways towards a resilient and sustainable industry that may not have otherwise been possible.

First published: 8 August 2017

<< News