Reach 10 - The Legacy of Censorship under Franco

Dìleab na Ceansarachd fo Franco

For the forty years between 1936-1978 every single book published in Spain had to be submitted to the Board of Censors. These censors could then decide whether the book was fit for publication, and wrote a report stipulating the necessary changes to be made. Some books were banned altogether. This rigid censorship of Spanish literary culture began under the regime of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Dr Jordi Cornellà, a lecturer in Hispanic Studies and Spanish at the University of Glasgow, wants to know what happened to the thousands of books which had been censored after the end of censorship in 1978.

For the forty years between 1936-1978 every single book published in Spain had to be submitted to the Board of Censors. These censors could then decide whether the book was fit for publication, and wrote a report stipulating the necessary changes to be made. Some books were banned altogether. This rigid censorship of Spanish literary culture began under the regime of Generalissimo Francisco Franco. Dr Jordi Cornellà, a lecturer in Hispanic Studies and Spanish at the University of Glasgow, wants to know what happened to the thousands of books which had been censored after the end of censorship in 1978.

In Franco’s Spain authors and publishers had to be very wary in their approach to four main subject areas. First, regarding religious issues because the Catholic Church was incredibly powerful at that time, and so discussing abortion, homosexuality, criticising the Church or anything which could be considered to subvert Catholic morality was forbidden. Second, historical issues were very sensitive had to adhere to the regime’s guidelines. In particular, the regime would only accept representations of Spanish history, especially depictions of the Civil War (1936-39). Third, in writings about society in general, one could not criticise the government or the army, nor could they discuss issues like poverty and human rights abuses because they supposedly did not exist in Spain. Lastly, political and ideologically themed literature which was not in line with the authoritarian regime was outlawed. Cornellà says the censorship was so suppressive that it became common for writers to publish outside of Spain in countries such as France, Mexico and Argentina.

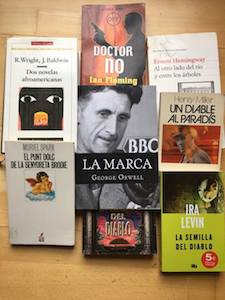

Cornellà’s work specifically focuses on books which were translated from the original English into Spanish. He is interested in comparing the newer editions to the original censored editions published in Franco’s Spain to discover what exactly has changed. Some books are being translated into Spanish for the first time, like Muriel Spark’s classic novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. However, as Cornellà has discovered many books by authors such as Ernest Hemingway, George Orwell, Ira Levin and James Baldwin are still being published in their censored form. Partly, because it is cheaper for publishing companies to reproduce the censored original versions as opposed to investigating the censor’s reports and producing a new edition.

Cornellà hopes that his research will encourage Spanish readers and publishers to consider the implications of reading and reproducing texts censored by the Franco regime. Cornellà has been interviewed in the likes of the Financial Times, the Sunday Times and on the BBC’s Today programme, and some Spanish news media outlets. Furthermore, Cornellà has been invited to numerous public events in the UK and Spain to give talks on the lingering impact of literary censorship under Franco. He usually points out to his audiences in Spain that they will own censored books, and that they probably bought some censored editions very recently. Even e-books are sometimes being published in their censored form.

Of course, Cornellà also appreciates that Spanish publishers might have a different perspective on the matter. Whist Cornellà would like to see the classics retranslated into Spanish for the benefit of a new generation of Spanish readers, that is not straightforward. Around half a million books were published in Spain between 1936-1978, based on the 500,000 censorship reports which have been archived. Publishers can also encounter legal issues when trying to deal with original manuscript material. However, there have been positive steps thanks to Cornellà’s work. A new edition of the complete works of Ian Fleming has been newly translated by its Spanish publisher, who acknowledged in the press that they had been inspired by Cornellà’s research. Francisco Calderón pointed out that ‘it is surprising that we can still find the censored versions of important literary works… There is still a lot of work to do and the new translations of Fleming’s works are a step in the right direction’.

If you'd like to find out more about this project or about working with an academic in Hispanic Studies you can contact us at arts-ke@glasgow.ac.uk.

If you wish to find out more about this article or about how you can progress your ideas (i) as an academic wishing to engage with a non-academic organisation or (ii) as a non-academic organisation interested in engaging with the academic knowledge base, please email the College of Arts KE Team.

<<Back to Reach 10